Mice on the move in Michigan, some "hitchhike," researchers say

Susan Hoffman, Miami University associate professor of biology, talks about how mice and other small mammals are moving northward in the Great Lakes region, in an apparent response to climate change. (Video by Margo Kissell)

By Margo Kissell, university news and communications

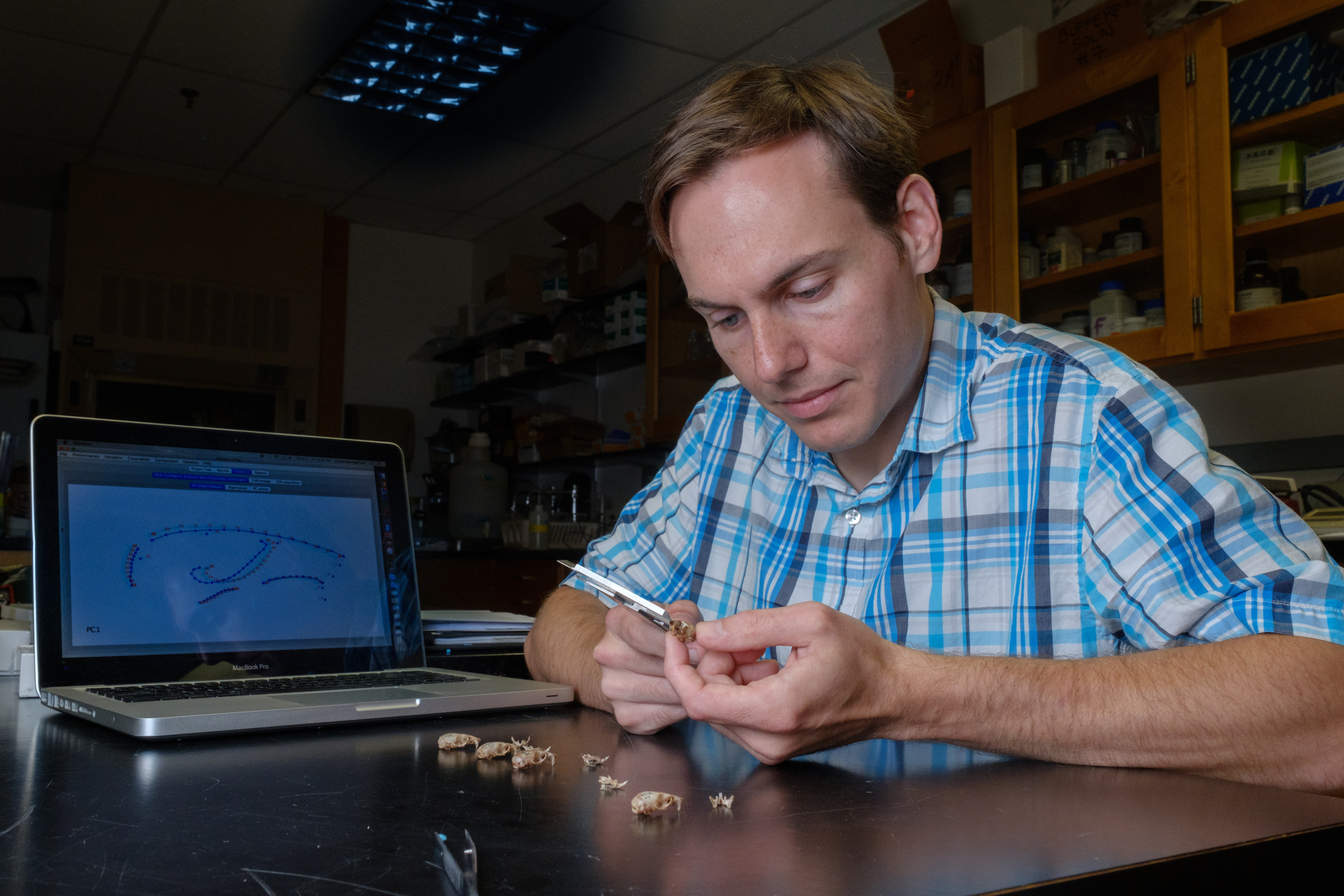

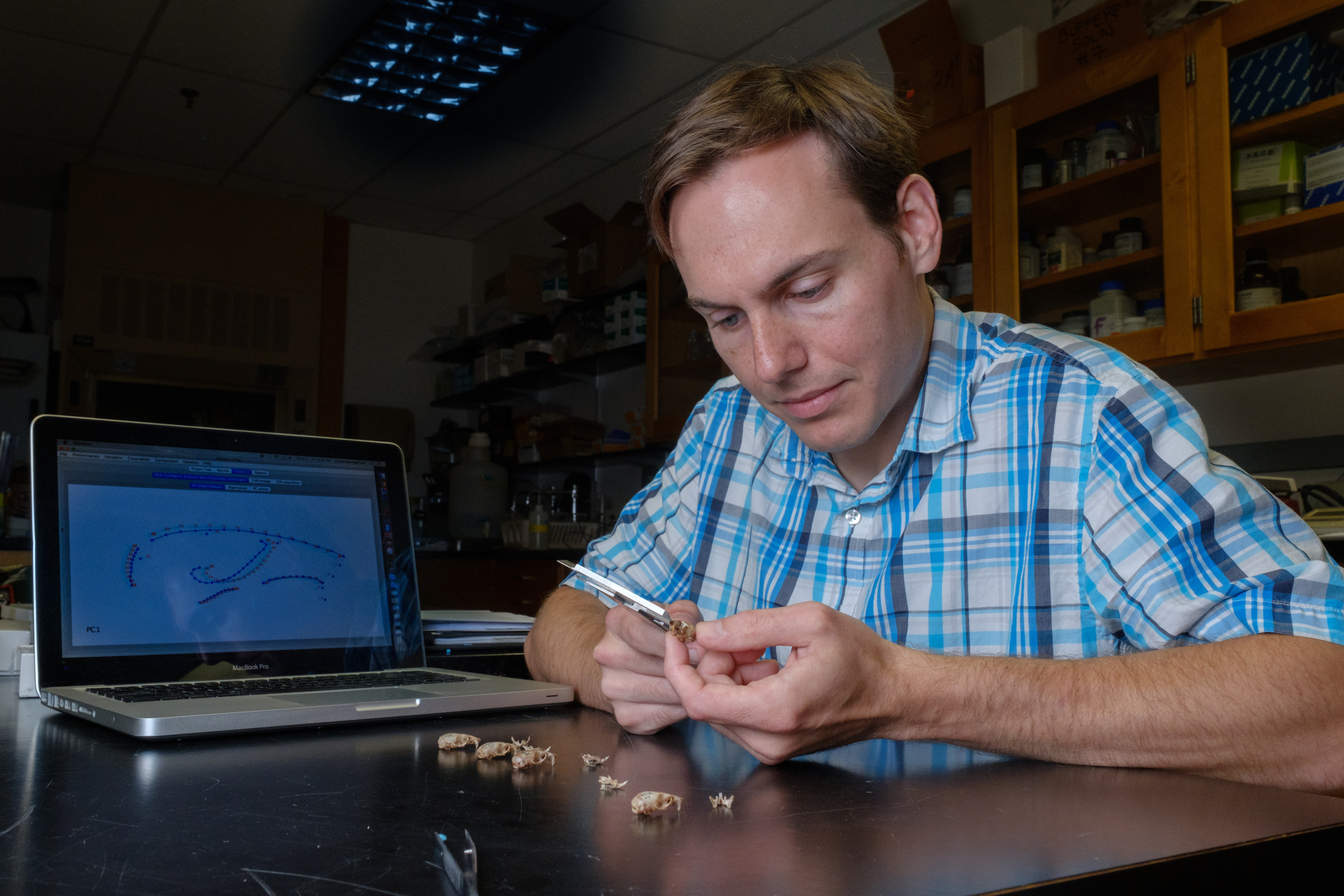

Jeremy Papuga knows that when most people think of climate change, they imagine huge polar bears on melting icecaps, not small field mice in forests in Michigan.

But in an apparent response to climate change, species are migrating, including the white-footed mouse (Peromyscus leucopus) that is moving northward into territory long occupied by the woodland deer mouse (Peromyscus maniculatus), said Papuga, a graduate student at Miami University.

He and Joseph Baumgartner — both pursuing doctorates through Miami’s evolution, ecology and environmental biology program — work closely with Susan Hoffman, associate professor of biology, whose lab focuses on the evolutionary genetics of mammals.

Hoffman and her students have studied this migration in the northern Great Lakes region, where some field mice and other small mammals are rapidly expanding their ranges northward. The work is in collaboration with researchers at the University of Michigan and Michigan State University.

The white-footed mouse has been pushing past a transitional forest region that has long served as a dividing line for many species.

In response, the woodland deer mouse is moving farther north to the coniferous boreal forest in Canada, or coexisting with the white-footed mouse.

Hoffman characterizes the white-footed mouse’s expansion as dramatic — about 125 miles in 30 years, 15 times farther than one would expect.

This migration also has been documented with other species, including chipmunks, flying squirrels and meadow-jumping mice, she added.

“Because it’s happening to many species simultaneously, we believe it’s tied to overall climate effects,” Hoffman said.

A white-footed mouse (Photos from Animal Diversity Web)

Documenting dramatic shifts since the mid-1980s

Hoffman has been researching these mice since 1985 when she was a graduate student at the University of Michigan, where she earned her doctorate in evolutionary genetics. That’s when she first started working with Philip Myers, who is now professor emeritus and curator emeritus of that university’s Museum of Zoology and still involved in the collaborative research.

“We just noticed we were not seeing the animals we expected to see based on records of what had been found previously at that location,” she said. “We were seeing the wrong kind of mice and we were seeing opossums, which should not be that far north.”

Hoffman, who joined Miami in 1995, began working with Myers again in 2001. She started doing some genetics on mice “because he was seeing unexpected patterns of where animals were. And so we started this project and have been chipping away at it ever since.”

Hoffman and colleagues at the University of Michigan and Michigan State have published their research several times since 2009, when they first documented the shift for various species based on historical data the University of Michigan had collected since 1900.

Baumgartner has been concentrating on the southern white-footed mouse that they informally refer to as the “winner” mouse, while Papuga has focused on the woodland deer mouse, the “loser.”

Hoffman said data collected over 15 years allows her graduate students and undergraduate students to do all sorts of comparisons, such as between where the mice coexist and where only one species lives; where they are existing under different ecological circumstances; and where they’re able to move versus where they haven’t been able to move because of natural barriers.

A woodland deer mouse

The Great Lakes appear to have constrained the movements of some mice in the Lower Peninsula, whereas in the Upper Peninsula, “the same mice with the same situation were able to take off like a rocket and take over all this new territory,” she said.A typical mouse disperses about a kilometer (.62 mile) within a generation after weaning from its parents, Baumgartner said. Trapping records and other observations show the mice from the Hiawatha Forest, in the southern-most tip of the Upper Peninsula, have moved throughout the entire northern peninsula.

However, the researchers believe not all of them are getting there on four legs.

Some of the mice appear to have “hitchhiked” across the Mackinac Bridge, a 26,372-feet-long suspension bridge that connects the Upper and Lower Peninsulas, Baumgartner said. They believe the mice are climbing into RVs and logging trucks that spend long periods of time in their habitat before moving on to other sites up north.

Studying the “loser” mouse

Year after year, Hoffman and her students return to several locations in Michigan to capture mice. They collect tissue samples and document other information (size, weight, etc.) before tagging their ears and releasing them back into the wild.

Jeremy Papuga holds a white-footed mouse that was a stowaway from his most recent trip to Michigan. He plans to return the mouse during a September trip. (Photo by Margo Kissell)

Papuga returned to Miami this week from his fourth Michigan trip this summer. He’s been studying reproductive timing to determine why the woodland deer mice are losing.

Some prior research has shown the “winner” mouse can reproduce earlier if it’s a warmer spring. “With climate change you get a higher percentage of warmer springs that allow them to reproduce earlier,” he said.

Their research findings of knowing where they are moving have practical implications because the white-footed mouse is a vector for different diseases, particularly Lyme disease.

Beyond that, Hoffman said the research has examined “a series of natural experiments that allow us to track a species that is expanding, that appears to be very directly related to climate change, and another that is contracting its range apparently due to climate change.”

And although neither species is endangered, she said, “it’s a way of trying to understand a model system that could tell us, how do you preserve species that are actually endangered?”

Hoffman is interested in the genetic capabilities of organisms that are under stress. She said you’d expect these small mammals to lose a lot of genetic diversity and become more homogeneous, but that doesn’t appear to be happening here. At least not yet.

“They still seem to be doing relatively well genetically,” she said. “What does it take to push a species over that threshold to where they are in genetic trouble?”