Hate math? Professors tackle arithmophobia with innovation

By Alicia Auhagen ’16, marketing and creative services copywriter

At the Southeastern Correctional Institution in Lancaster, Ohio, inmates lined up eagerly at the door. It was 1992 and the students arrived before their instructor, Todd Edwards, to fractions class.

Qualifying to take college courses while incarcerated was no easy pursuit. You had to be a good student and reasonably intelligent.

Edwards, now professor of mathematics education at Miami University, was dumbfounded by their enthusiasm. One day, he finally asked: why are you so eager to be in my class? They responded, “Todd, it’s an escape for us. This class is freedom.”

Three years later Edwards was teaching math to freshmen at Upper Arlington High School near Columbus, Ohio, and witnessed a different phenomenon. Kids lined up at the door to escape class.

One day, he finally asked: why are you so eager to get out of my class? They responded, “Todd, school is a prison. We just want to be free.”

Todd Edwards works with math education students to develop lesson plans for middle schoolers.

What is math, really?

His contrasting teaching experiences illustrate our complicated relationship with math. For him, it’s a relationship that raises an important question: what is math?

When we think about math, we often refer to school math. School math problems can typically be completed in a few minutes and are usually solved individually. There may be a significant amount of symbolic manipulation involved. The teacher might ask only for the correct answer.

But Edwards and Dana Cox, associate professor of mathematics at Miami, see a different perspective. Much in the way that writing is not the finished piece, math, the professors believe, is not the final answer.

“The mathematics is in the middle,” Cox said. “It’s the juicy stuff before you get to the answer.”

The math problems Edwards enjoys can take months to study. And they’re certainly not solo endeavors. He bounces ideas off colleagues or recruits others to help him find solutions.

Some math problems are pondered for years, even centuries, and many are still without answers. These challenges require an approach rarely seen in the math classroom: long-term collaboration, analysis from multiple viewpoints, and celebration of the process.

Dave Sobecki teaches math in interactive, and often edible, ways.

Visualize this: math’s role in healthy democracy

Dave Sobecki, professor of mathematics on Miami’s Hamilton campus, stresses the importance of basic math proficiency in a monetary-based society.

“If people don’t have any understanding of basic numeracy and problem solving, they’re just begging to be taken advantage of. I really believe that to be successful in modern society, the ideas that we learn and are exposed to in mathematics are essential,” he said.

It’s all about quantitative literacy, which Cox defines as the ability to read and write your world through mathematics.

From Fitbit data to poll results and advertisements, data visualizations are everywhere. The ability to interpret data contextually and critically is a skill that should be emphasized in math curriculum if students are to become informed citizens in a healthy democracy, the professors believe.

Uncovering our arithmophobic roots

Our experiences in the math classroom largely influence our perceptions of the subject long after schooling, Edwards said. Cox believes one reason for this is that mathematics is a status giver. When a student is good at math, they are also deemed smart by those around them.

This perception, whether the individual wants to be considered smart or not, gets internalized and becomes part of their identity. So when adults say they’re not good at math, they give the children around them permission to also make that claim. And so begins the mindset that being good at math is like a switch – something you either are or aren’t. It’s a harmful cycle, Cox said, that reflects a need to expand our sense of what it means to do math and be good at it.

You probably do math every day without giving it much thought. You calculate a tip at a restaurant. You make a budget for the month. You do a Sudoku puzzle. You estimate the amount of time it will take to get where you need to go.

“We need to stop equating math with this super-genius-level activity and bring it to the point where everybody recognizes that a mathematic outlook is possible,” she said. “Everyone is a mathematician.”

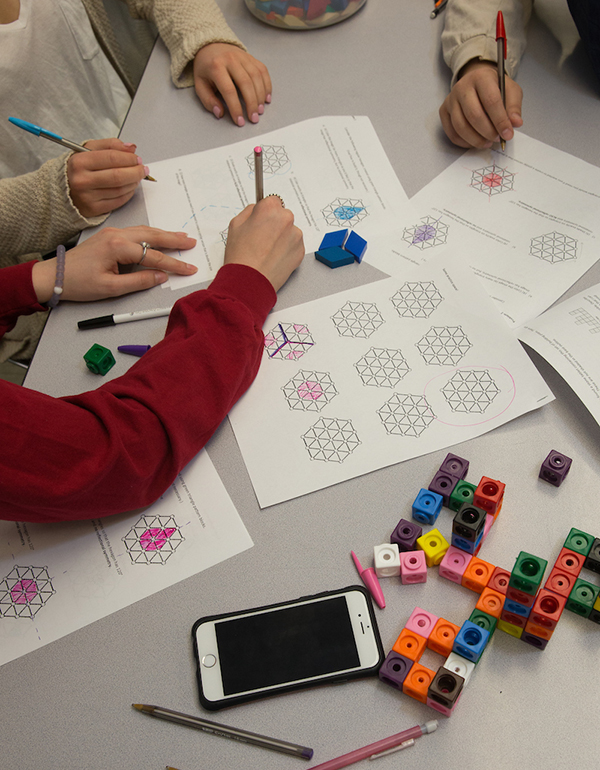

Dana Cox’s students create work that is mathematical and artistic.

Math education reimagined

Robyn Barnard, engineering management and mechanical engineering double major, entered Sobecki’s math class intimidated and unsure of her math skills. A non-traditional student, Barnard hadn’t seen classroom math in more than a decade.

But “Dr. S”, as the students affectionately refer to him, makes it his mission to creatively portray mathematical ideas. He introduces concepts to students in practical – and edible – ways. Like melting a chocolate bar in the microwave to calculate the speed of light.

By the end of the class, Barnard felt increased confidence in her math skills.

“I realize that math does not need to be difficult. With supportive guides such as Dr. S, I feel certain that most any student can engage in math more confidently,” she said.

Her story points to the innovations happening in math classrooms today and educators’ vigilance in challenging student assumptions of what math is.

Cox employs what she calls “rough draft thinking” in her math classes. She doesn’t lecture and a lot of the learning happens out loud. Students get into groups to work on a problem, and in the middle of discussion, she’ll tell them to freeze and talk to someone outside their group about what they’re thinking, where they’re at with the problem, and what’s bothering them about it.

“Treating mathematics as something that’s not complete yet frees people up to talk about more conjectures and possibilities,” she said.

Edwards is working with math education majors to develop lesson plans for sixth graders that integrate math, history, and technology for the Connected Mathematics Project (CMP). The CMP, spearheaded by Michigan State University and funded by the National Science Foundation, is a collaborative effort between teachers and students to develop mathematical communication and reasoning skills and to foster awareness for the connections between math and other disciplines.

The lessons Edward’s students are preparing will be shared with the creators of the CMP and teach middle schoolers that there are real people behind the concepts they’re learning – pioneers like John Gaunt and Florence Nightingale.

These innovative techniques bridge the gaps between academic disciplines and help students conquer their fears about math.

For Sobecki, his teaching is also about making an impact.

“I want to know that when my teaching career is done, there are a handful of people out there that I really made a difference for – that my ways of thinking really changed their lives for the better,” he said.