Racial Literacy Matters: Why the Dialogue Around Equality and Inclusion Must Evolve

James M. Loy, Miami University's College of Education, Health, and Society

“What do you do?” was the impassioned question that resonated, again and again, throughout the captivated audience of Miami University students, staff, and faculty.

What do you do, they were asked to consider, when a racial slur sparks a serious organizational controversy and forces difficult, sometimes confrontational interactions. Or when, for example, buildings are defaced with derogatory epithets or offensive symbols? Or when a growing culture of systemic inequalities, hidden biases, and unconscious microaggressions result in undeniably clear disparities between certain groups?

“What do you do when you are confronted with these issues?” Dr. Shaun Harper, race and gender expert and renowned University of Pennsylvania professor, asked during his interactive talk titled, “Racial Literacy as an Essential Skill for Student Affairs Professionals.”

According to Harper, who also serves as executive director of the Center for the Study of Race and Equity in Education, most people have no good answers to such a simple question. And this, he stresses, marks a glaring and unhealthy trend in a society still struggling to both understand and overcome issues that continue to prohibit true diversity and inclusion.

“It is not just about talking about race and talking about racial problems and racial realities,” Harper says. “Nor is it just about understanding one’s racial identity and how that identity co-mingles with other identities and how one identifies race in one’s own social history, or racial development journey. All that stuff is really important. But it can’t just be that. It also has to be about skill building.”

All across college campuses, public institutions, and even private businesses, issues centered squarely on race, inequality, and social injustice continue to arise. Sometimes these problems explode into highly charged episodes that are captured prominently in the national spotlight. But far more frequently they are more subtle and silent, and perpetuated through no nefarious will or active maliciousness of any particular individual or group.

In these instances, inequities are unconsciously reproduced through a tacit reluctance, or even an admitted inability, to open engaging dialogues around important topics that are deemed by many to be just too uncomfortable.

“It creates this cultural norm in many departments where we just don’t even go there,” says Harper.

Across Miami University, this idea is most clearly echoed by the College of Education, Health and Society (EHS), which considers promoting diversity and inclusion to be among its highest priorities. Though EHS, too, is also very aware of the social barriers that continue to impede progress.

“Any discussion about race often is very difficult because people honestly don’t have the language to appropriately talk about race, because within the conversation is always the intimidation that one is going to be offensive, and offended, by what is going to come out of the conversation,” says EHS Dean Michael E. Dantley. “And so then substantive conversations just aren’t held. And because they are not held, we remain complicit with the racist kinds of things that are happening in any institution.”

This results in what Harper calls “codes of racial silence.” Such codes are typically adopted by people, or even entire organizations, that inadvertently maintain biased status quos. And it’s a cycle, Harper argues, that will only be broken once racial literacy becomes more seriously recognized, accepted, and taught as an essential skill.

“We can’t even do racial equity if we don’t even know how to talk about race,” Harper explains. “Racial literacy is an actual form of literacy. It is about being able to read, both in actual literature, and also how to read situations and read people. But more fundamentally, it is also about how you talk comfortably and competently about racial realities in classrooms and departments and workplaces and student affairs divisions, and so on.”

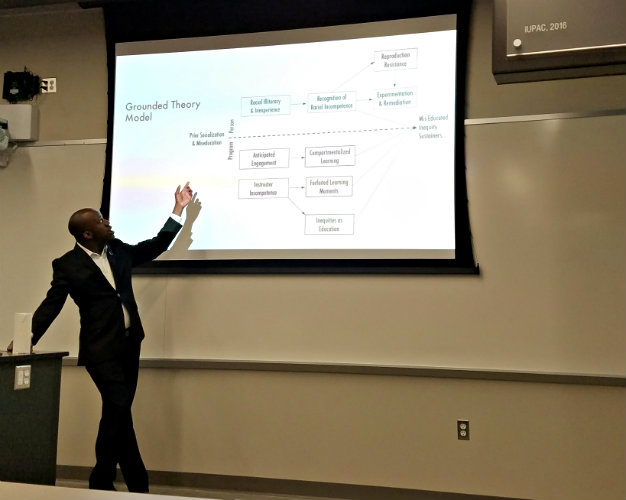

Many of these ideas have recently crystalized for Harper after completing an intensive research

project to explore what methods were used to prepare future professionals to work with racially diverse populations, to close achievement gaps, to increase retention and persistence among students of color, and to end enduring racial inequities.

“I was essentially interested in what people learn in their graduate programs about race, and their feelings of preparedness to deal with very complex, vexing racial problems on college campuses,” Harper says.

To do so, he collected data, in part, from current graduate students studying student affairs, as well as early career student affairs professionals who were already working in the field.

And after five years of exploring how graduate preparation programs (at 14 of the largest producers of student affairs professionals in the country) facilitated shifts in attitudes and assumptions about race and inequality, the results clearly showed a need for a substantial amount of improvement.

Prior to entering their graduate programs, many students reported feeling inexperienced about issues of race and inequality. But they also looked forward to what Harper called “anticipated engagement” with the subject. That is, due in large part to various graduate program marketing campaigns that promised immersion in diversity-related topics, these students expected to learn more.

Though in reality, however, aside from a limited number of obligatory and surface level diversity courses, more meaningful engagement was rarely, if ever, achieved.

“There was almost unanimity here that unless someone was an ethnic studies major or unless someone had slipped and fallen into a sociology of race course, they didn’t really learn about race anywhere else throughout the undergraduate curriculum,” Harper says. “For the few who had, they were very self-directed. It wasn’t like there was an educational and curricular plan to ensure students were learning about race and social justice and people of color.”

Even the early career professionals -- who had already been on the job for approximately five years and were chosen by Harper specifically because of their prestigious status as recent ACPA: College Student Educators International and NASPA: Student Affairs Administrators in Higher Education award winners -- felt unprepared for the realties they encountered.

“These people, who were exceptional professionals, confessed to us, unashamedly at times, ‘I still don’t know what to do,’” says Harper.

“We would ask them,” Harper continues, “‘Give us some examples of some racial situations or some particularly tense racial moments.’ So they did. But then they said, ‘I certainly don’t know what to do when someone spray paints the N-word on a black student’s residence hall door, or defaces the Latino student cultural center, and so on.’ But, again, remember, these are exceptional standouts. How do they not know what to do? Because they had never learned how to do these things.”

For Harper, then, it is critical that these skills are taught, and not just as part of a vaguely overarching adherence to a philosophy that pays lip service to diversity and inclusion. Rather, he envisions a more systematic approach that deliberately and meaningfully infuses entire curriculums with actionable ways to be proactive, preemptive, and preventative.

Solving this problem may not be easy, and it will not happen overnight, but Harper does offer some practical suggestions to at least start moving in the right direction.

He recommends reading relevant books such as Engaging the “Race Question'' by Alicia Dowd or Race Talk and the Conspiracy of Silence by Derald Wing Sue, for example. And he wants us reading not just as individuals, but as groups, before then participating in interactive discussions as a department, division, or office.

He recommends paying attention to what happens elsewhere in the country, and engaging these issues in staff meetings to consider what could be done should similar incidents occur locally. And he recommends using cultural climate data more responsible. Rather than simply collecting such data and promptly shelving it away after a cursory glance, Harper wants it to become more public, talked about, and continually improved upon.

Finally, he also recommends being honest about identifying and rectifying our hidden biases, regularly attending race and identity conferences such as NCORE, and even hiring a professional facilitator to start meaningful dialogues if necessary.

Back at Miami, students, faculty, and staff members across campus can look toward EHS to lead many of the transformations that are more reflective of our increasingly global community, to make the changes needed to establish the holistic, integrated, and ethical educational approaches that Harper, as well as many others, know that society so desperately needs.

“We have major players in EHS whose focus has been on race,” says Dean Dantley. “Their research has been on race. The research has been on social justice. Often courses that are taught here are grounded in notions of social justice and racial equity. So I think that our college is well positioned to begin, as Dr. Harper calls it, a more salient conversation about race.”

Among those advancing this conversation is Dr. Stephen Quaye, EHS associate professor in the department of educational leadership, who leads classes in Miami University’s own Student Affairs in Higher Education (SAHE) graduate program including those that focus on critical methods to engage difficult issues surrounding race, class, privilege, and power.

According to Quaye, recent progress throughout the student affairs graduate program has been comprehensive, and in ways that are relevant both inside and outside the context of classroom-based learning. For one, by actively recruiting and retaining more students of color, EHS has made quantifiable strides to diversify SAHE’s demographics. So now, when compared to previous years, current percentages have increased significantly.

“We now enroll more than half of students of color, which, to me, is a dramatic shift from my first year here,” Quaye says. “That is a dramatic shift of not only actually recruiting, but also actually graduating and retaining more students of color. And then, our curriculum is also attuned to racial justice issues. I teach a course specifically about engaging issues of race in the classroom where students try to develop the racial literacy that is so critical for student affairs educators.”

In his Diversity, Equity, and Dialogue course, for example, Quaye teaches students how to practice self-awareness, the important differences between shame and guilt, how these feelings are manifested in certain dialogues, as well as how to resist becoming defensive when confronted with biases, assumptions, stereotypes, or even overt racism.

Beyond his efforts in SAHE, Quaye, along with three other EHS colleagues in the departments of family science and social work and educational psychology, have also recently secured funding to start a new project titled, “Incorporating Diversity and Inclusion in EHS Classrooms: An Opportunity for Interdisciplinary Learning and Strategy Sessions.”

“It is a group of us who are trying to introduce diversity, and interweave it more throughout the program,” Quaye explains. “We are trying to develop what will essentially help students who have different identities succeed. It is really cool because it combines different departments, and it is another example of putting into practice some of the things Shaun Harper talks about. It recognizes that we can’t do it by ourselves. We have to work together in order to address race and racism.”

So far, this particular EHS project is in very nascent stages, but it is also in line with others that are already in motion. Another project, born from a similar emphasis on interdisciplinary cooperation, is ambitiously poised to eventually redefine the entire EHS teacher education curriculum.

It’s called the “Interdisciplinary Teaching and Curriculum Grant” and it focuses on the cultural and social realities of contemporary education and schooling.

Starting with EDT 190, an introductory teacher preparation course, the project hopes to change the way future teachers will successfully manage increasingly diverse classrooms. By introducing issues of race, class, equality, and gender, the changes to EDT 190 are already underway, but similar changes to more advanced teacher educations courses will soon follow.

For Ganiva Reyes, EHS Visiting Assistant Professor and Heanon Wilkins Fellow, the interdisciplinary grant is not only about helping students think critically about the forces that perpetuate inequality and inhibit inclusiveness, it is also about “centralizing culturally relevant teaching and social justice into the entire teacher preparation program.”

For EHS, it’s one more way the college is moving toward increased racial literacy, particularly in the classroom. However, as Harper points out, this conversation is not just about the students. So every week, the dean’s office also sponsors a regular writing group, which provides a unique space for faculty to come together, to collaborate, to share ideas, and talk.

“It is mostly made up of assistant professors, a lot of whom are people of color, and the dean provides lunch,” says Quaye. “It seems so simple, and yet so few places actually do things like that. Just having the space to get together, to write on a weekly basis, it helps build a community among other faculty of color who are then able to engage with people outside of that space.”

If we are ever to break the codes of silence that still pervade most organizational cultures, it is clear that such efforts need to take place. And throughout EHS, this conversation has, at least, begun. The students and faculty are talking, they are learning how to engage with difficult social issues, and, from a much larger perspective, the work of transforming the curriculum in socially conscious and culturally relevant ways is underway.

This is crucial work, and it’s a good start, but there is undoubtedly so much yet to be done. And not only for EHS, but for all institutions hoping to overcome one of the most challenging issues of our time. Otherwise we, all of us, will only continue to remain complicit in a system that sustains and reproduces social injustices year after year after year.

But breaking this cycle will require real effort, a conscious determination, an ability to teach effectively, and, especially, a willingness to actually learn how.

“The inequities are not going to close themselves or correct themselves,” says Harper. “How do we be sure that we have created a work place that is inclusive and responsive? We literally teach people how to talk about race, as well as how to do racial equity.”