War and revolution from a Russian perspective: Havighurst Center holds symposium on the Blavatnik Archive

Written by Rebecca Huff, CAS communications intern

Three scholars of Jewish history visited Miami on Friday, November 3 to discuss how specific events from the Russian Revolution and WWII had profound impact on the lives of Jewish soldiers and civilians in a special symposium entitled War, Revolution, and Jewish Life.

The symposium, organized by the Havighurst Center for Russian and Post-Soviet Studies, complemented the University Libraries' special collections exhibit Blood in the Snow: Russian Revolution and the Civil War, 1917-1920, which will be on display until December 20 as well as the New York City-based Blavatnik Archive, on display in the front lobby of King Library until November 20. [See the October 2017 Miami press release Exhibit from New York City-based archive visits King Library.]

Blavatnik Symposium guest speakers (left to right): Eugene Avrutin, Anna Shternshis, and Jeffrey Veidlinger

"The special collections exhibit is a part of our event to commemorate the 100th anniversary of the Russian revolution," explained Masha Stepanova, coordinator of cataloging and Slavic librarian for University Libraries. "Our exhibit of the Blavatnik Archive focuses on interviews and stories of Russian Jewish WWII veterans."

"The events of 1917-1920 still matter to how we can understand the world today," said Stephen Norris, professor of history and interim director of the Havighurst Center. "For our symposium, we were fortunate to bring in three experts who have all worked in the Blavatnik Archive, to talk about their work and add rich contextualization to the information in the exhibits."

Anna Shternshis, the Al and Malka Green Associate Professor of Yiddish Studies at the University of Toronto; Jeffrey Veidlinger, the Joseph Brodsky Collegiate Professor of History and Judaic Studies at the University of Michigan; and Eugene Avrutin, associate professor of modern European Jewish history at the University of Illinois each covered facets of the topic by providing harrowing accounts of stories they had collected from their research.

"In a sense, our speakers picked themselves because their research has helped to redefine the ways we understand these histories and cultures depicting Russian Jews," Norris said.

"A Tale of Two Murders: The Velizh and Beilis Blood Libel Cases"

Professor Avrutin opened the symposium by discussing two cases of ritual murders in Imperial Russia that were blamed on Jewish citizens. Even though in both cases they were eventually acquitted, suspicion was still high. As Avrutin noted, these cases — one in 1825, one in 1913 — provided important context for the violence that would be directed at Russia's Jewish populations during the 1917 revolutions.

Blavatnik Symposium audience

One of the cases concerned the 1823 murder of a 3-year-old boy in Velizh. His body was found in the woods mutilated with over a dozen puncture wounds. The case was investigated twice, the first time lasting roughly a year and a half and the second time 10 years.

"This is probably the longest ritual murder case in world history," Avrutin said. His book, The Velizh Affair: Blood Libel in a Russian Town (to be published in 2018) dives deeper into this case.

The second trial in 1825 went all the way to the Supreme Court, but even then there was a split decision. He read to the audience what Tsar Nicholas I wrote: "I do not have and indeed cannot have the inner conviction that the murder has not been committed by Jews."

Avrutin explained that Nicholas believed that since there were sects of radical Christians who castrated themselves for religious reasons, then there could be sects of Jewish citizens who killed young children for religious reasons as well.

"The idea is that maybe these Jews in Velizh didn't do it, but certainly some other Jews could do it," Avrutin said.

The Velizh Affair, he concluded, influenced the Russian state's suspicions of its Jewish population, which in a similar case in 1913, nine decades later, remained extremely vulnerable to accusations of wrongdoing and was seen to be a potential enemy within. These attitudes persisted after 1917.

"And Then I Killed Him: Red Army Soldiers Speak of the End of the Holocaust"

Professor Shternshis followed by telling the audience about her interview with "Victor," a Jewish veteran of the Soviet Union's Red Army. He was drafted in 1936 and came back to find that his entire family had been killed. To make matters worse, it was a neighbor that had helped direct Nazi soldiers to his family's house.

Victor was thirsty for revenge but could not find the accomplice. He told Shternshis in an interview that "no one paid for what they've done to the Jews."

Through Victor's story, Shternshis captured the guilt a lot of Russian Jewish soldiers felt after the war. She explains that this guilt stems from "being able to protect everyone but his own family."

As Victor told her, "people don't make choices to kill; it's by chance."

"A Kind of Victory? The Return of Jews to Small-Town Ukraine"

For his talk, Professor Veidlinger described to the audience a different reality for Jews in the Soviet Union.

"It's a sudden act of violence," he said.

Veidlinger told the story of Bella Vaisman, an 8th-grader whose visit with her grandmother turned into not only a reward for her good grades but also a saving grace.

On June 20, 1941, Bella was sent to her grandparents as a gift for her doing well in school. Just three days later, however, Germany invaded the Soviet Union, making communication and traveling more difficult. The Archives of Historical and Ethnographic Yiddish Memories (AHEYM) translated letters and telegrams from Bella's parents, who desperately tried to keep their daughter from coming home because they knew she was safer with her grandparents. But by July, the letters suddenly stopped.

"It's a lesson in how things can change on a dime," Veidlinger said. "Bella had a wonderful life before and up until June 1941. Imagine that your entire community is destroyed and you're sent away. You think you're just going for a week to visit your grandparents."

Following the symposium, freshmen Pavlo Stasiouk and Helen McHenry, both majoring in international studies and Russian, Eastern European & Eurasian studies (REES), said that they found the talks enjoyable and educational.

"I thought it was very enlightening," Stasiouk said. "Especially with Jewish history we forget that there is an Eastern portion to that history, and that a lot of our understanding of Jewish history is from a Western perspective."

McHenry said that she was particularly fascinated by the ritual murders that were discussed in Avrutin's talk.

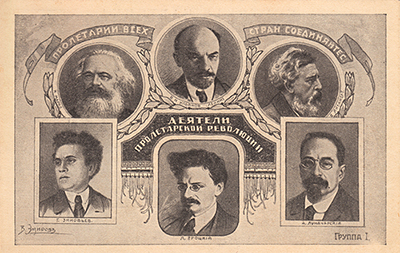

Postcard featuring prominent members of the Bolshevik Party

"Being Catholic, I have a high opinion of Judaism, and to see that other people assumed they were sacrificing children for their rituals was odd," McHenry said. "I've never thought about that before."

"The Russian revolutions of 1917 were the most significant events of the 20th century," Norris said. "They had echoes and reverberations throughout the world at that time and ever since. The first attempt to build a socialist system, the subsequent rise of fascism, the Holocaust and horrors of World War II, the tragic exportation of the Soviet model to other parts of the world, the decolonization of the world after World War II, the Cold War, the new nations created in the wake of the Soviet collapse: these events and more all stemmed from 1917."

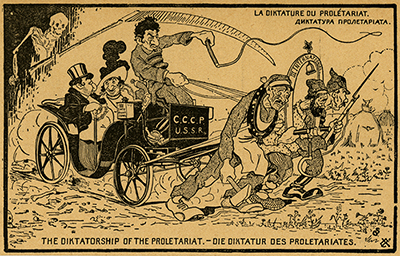

Anti-Semitic postcard depicting revolution controlled by Jews

He pointed out that among the most interesting items on display in the Miami exhibit are two groups of postcards: those from Jewish revolutionaries from the Bolshevik Party that seized power in October 1917, and a set of anti-Semitic postcards portraying negative depictions of these revolutionaries.

"These postcards help to connect the dots between the exhibits and the symposium," he said. "They reflect the attitudes that persisted towards Russian Jews since the Velizh Affair in 1823 to well over a century later."

Miami's Blavatnik Archive Symposium was a collaborative effort by the Havighurst Center, Hillel at Miami University, and University Libraries. Special thanks go to the nonprofit Blavatnik Archive, founded by Len Blavatnik.