Miami University Social Justice Studies class connects with death row inmate

To explore the concept of restorative justice for the students in his introduction to Social Justice Studies class, visiting instructor Mark Curnutte brought in a voice from Ohio’s death row.

Miami University Social Justice Studies class connects with death row inmate

By Margo Kissell, university news and communications, with Mark Curnutte, visiting instructor of Social Justice Studies and Journalism

To flesh out the curriculum of his social justice courses and give shape to its concepts, visiting professor Mark Curnutte (Miami ’84), pictured below, often draws on his experiences as a former journalist who reported extensively on social issues of race, class, poverty, homelessness, and immigration. He will speak of the people he met, the lives they built, and the societal factors that worked for and against them.

Mark Curnutte

To explore the concept of restorative justice for the 49 students in his introduction to Social Justice Studies class, he brought in a voice from Ohio’s death row. Keith LaMar — in solitary confinement at the Ohio State Penitentiary in Youngstown and scheduled to be executed on Nov. 16, 2023 — recently spoke to Curnutte’s students in Upham Hall via a phone call put on speaker.

“The basic idea of restorative justice is to bring the offender, victims and community together for healing,” he said. “In terms of the offender, the relationship is that no life is without merit and potential redemption.”

Curnutte noted that the context of the visit from LaMar “wasn't focused as much on his guilt or innocence but on his ability to make something of his life — restoring it — even as he was on death row. The larger course lesson was on the social movement of restorative justice, both in and outside of prison.”

Living on death row

LaMar was sentenced to prison in 1989 in his native Cuyahoga County after fatally shooting a man who LaMar said was trying to rob him. He pleaded guilty to murder and was sent to the Southern Ohio Correctional Institution in Lucasville for 18 years to life. He was 19 at the time.

In early 1993, an 11-day riot broke out at the prison. It resulted in the deaths of nine inmates and a prison guard.

LaMar was convicted of aggravated murder in 1995 in the deaths of five of those inmates. He maintains his innocence, arguing that as a Black man, he was denied a fair trial by the all-white jury.

LaMar was convicted of aggravated murder in 1995 in the deaths of five of those inmates. He maintains his innocence, arguing that as a Black man, he was denied a fair trial by the all-white jury.

He has sought to have his convictions and death sentence overturned. The courts have rejected those arguments. He told the Miami students what it was like learning that the Ohio Supreme Court had set his execution date.

"I was devastated, of course, but it galvanized what I'd been doing," he said.

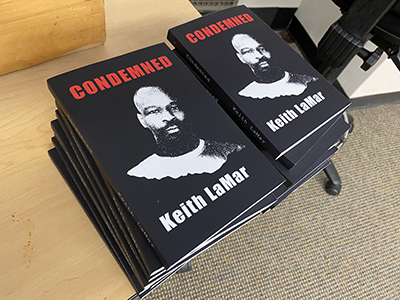

What LaMar has been doing is sharing his story, in large part through his self-published book, Condemned, which the class read.

"I had to teach myself to write," LaMar told the students. "My mentor ... told me I have to stand up and speak for myself. That book is my story. That book is my life."

LaMar wrote in stream-of-consciousness fashion, "going back through the wreckage of my life growing up in poverty, drugs, crime, violence. The book has allowed me to go places I am not allowed to go. I might be executed. It will not be because I did not try to tell my story."

He said he has spent the past three decades learning "everything I can about the law, social justice, the society we live in.”

Connecting with Miami alumna Rachel McMillian

Books, he said, changed his life. He has memorized parts of favorite author Richard Wright's memoir, Black Boy, one of an estimated 1,000 books he said he has read in prison.

LaMar started a literacy program for youth in juvenile detention facilities called Native Son, taken from the title of a Wright novel about a Black man named Bigger Thomas who grew up in poverty on Chicago's South Side in the 1930s.

In his limited time outside solitary confinement, he speaks to college and high school students via Zoom or phone calls.

"When you learn, it puts you in a better situation to make better decisions," he told the students. "It's better to have some choice than no choice. It's better to have your eyes open than shut."

Rachel McMillian

Curnutte learned about LaMar from Miami alumna Rachel McMillian (Miami ’09, MA ’12, PhD ’21), pictured at right, who recently collaborated with LaMar on a prisoner-led book club with Aiken High School students.

Now an assistant professor at the University of Illinois, McMillan previously taught at Aiken in the MU Teach program, a partnership between Miami and Aiken that aims to inspire more students of color to become educators by emphasizing culturally relevant teaching and critical conversations about race, gender, and equality, as well as Black history and Black culture.

When Curnutte learned about McMillian’s efforts with LaMar, he planned for his class to learn LaMar’s story because he saw potential learning outcomes.

Introduction to social justice studies is about “complicating students’ thinking,” Curnutte said.

Two of the stated goals in Curnutte’s syllabus are for students to be able to articulate the social and economic causes of social injustices and coherently articulate informed positions about controversial issues in a respectful way.

“Hearing directly from a man on our state’s death row, understanding his life and story and what put him there, I believe, helps to achieve these goals — especially when students then reflect on their learning in open-ended writing assignments.”

Sharing their takeaways

First-year marketing major Aaron Mallinger wrote in his reflective essay he was struck by the difference between LaMar’s first-hand account of life in prison compared to what he has seen in movies and on TV shows.

“I can’t imagine what Keith has gone through to get up to this point,” he wrote, “and I applaud his drive and bravery to continue to fight for himself despite all the world has thrown at him.”

Katie McSwain, a first-year international studies major, wrote a letter to LaMar as her reflection essay with the hope that it will be sent along to him.

“I just finished reading a copy of your book, Condemned, and I would like to say that I am truly in awe of the strength, power, and candid expression of the story which you have shared. As I read, I found myself awestruck at your ability to find hope in moments that would seem eternally dark to any other person.”

McSwain added, “The power, motivation, and strength of your book and your story reminded me to be not only cognizant of the humanity of those around me, but actually intentional about acknowledging it. As people of the United States, regardless of our background, we should be treated as such: people, with lives, spirits, hopes, dreams, and desires.”

LaMar wrote back to McSwain, thanking her for reaching out and sharing her heartfelt words.

“Obviously, I don’t take it lightly that you responded to what I wrote (spoke); the fact that it resonated means you on some level have the capacity to relate, which, at the end of the day, is my ultimate hope.”