About

Mission, Vision, and Core Values

Mission: The Mission of the Turrell Herbarium is to be a secure specimen archive and abundant resource for teachers, scholars, and afficionados to explore the broad diversity of fungi, algae, mosses, and vascular plants.

Vision: The Turrell Herbarium strives to grow into a preeminent resource for specimen conservation, conservation research and education of plant diversity.

Core Values:

Advance undergraduate engagement through teaching, events, and training

Advocate for university and community participation through outreach and volunteering, research, and visitation

Promote inclusivity, respect, equal-access, openness and authenticity

Meet Our Director

Li Zheng, Director and Assistant Professor of Biology

Li Zheng, Director and Assistant Professor of Biology

Li studies eukaryotic genome evolution and how it impacts phenotypic evolution and generates biodiversity. He is interested in using plants and insects as study systems to understand evolutionary processes, especially gene and genome duplication, chromosomal evolution, and horizontal gene transfer. His ongoing and future research aims are to investigate (1) the genomic basis of evolutionary innovations; (2) the processes of duplicate gene retention and loss; and (3) Why genome duplication is rarer in animals relative to plants.

History of the Herbarium

The Willard Sherman Turrell Herbarium of Miami University had its official beginning in 1906 with the appointment of Bruce Fink, eminent lichenologist and mycologist, as the first professor of Botany at Miami University, though an herbarium had previously existed in the 1870's, during the time Joseph James was teaching botany and geology at the university.

The Willard Sherman Turrell Herbarium of Miami University had its official beginning in 1906 with the appointment of Bruce Fink, eminent lichenologist and mycologist, as the first professor of Botany at Miami University, though an herbarium had previously existed in the 1870's, during the time Joseph James was teaching botany and geology at the university.

After Dr. Fink’s death in 1928, most of his priceless collections were sold to the University of Michigan. However, over 2,000 lichens and 3,000 fungi remained at Miami University, along with a small collection of vascular plants. Arthur T. Evans succeeded Fink and encouraged many students, including Elso Barghoorn, Charles Heimsch, Vernon Cheadle, and Richard Howard to collect plants and add them to the herbarium. Ethel C. Belk, one of Arthur J. Eames' students, functioned as curator from 1933 until 1956. Harvey A. Miller arrived at Miami University in 1956 and as curator began the development of an active exchange program that led to significant growth in the herbarium.

In 1965, it was learned that the oldest and largest herbarium in Ohio, that of Oberlin College (OC), was to be sold, at least in part. Miller and department chairman Charles Heimsch were successful in persuading Miami University that this collection should remain in the state and that it would be a significant addition to the original Miami University holdings. The Oberlin College collection, minus most its Ohio specimens, was purchased in 1966 with a gift from Elizabeth P. Turrell, and the herbarium was later named in honor of her uncle, Willard Sherman Turrell, a Miami University graduate.

Curators

| Bruce Fink, Curator (1906-1927) |

| Arthur T. Evans, Curator (1927-1929) |

| Ethel C. Belk, Curator (1929-1956) |

| Harvey A. Miller, Curator (1956-1967) |

| W. Hardy Eshbaugh, Curator (1967-1968, 1978-1982, 1989-1993) |

| Will H. Blackwell, Curator (1968-1978, 1983-1986, 1988-1989) |

| Wayne J. Elisens, Curator (1982-1983) |

| R. James Hickey, Curator (1987-1988) |

| Michael A. Vincent, Curator (1993-2022) |

|

Gretchen Meier, Curator (2022-Present) |

- Anonymous. 1974. Miami's outstanding Herbarium. The Miami Alumnus 28(2): 2pp.

- Barneby, R. C. 1964. Atlas of North American Astragalus. Parts I & II. Mem. New York Bot. Gard. 13: 1-1188.

- Cusick, A.W. and J.A. Snider. 1982. Survey of the herbarium resources of Ohio. Organization of Herbaria in Ohio, Columbus. Mimeo, 43pp. (publication funded by the W.S. Turrell Herbarium Fund of Miami University)

- Cusick, A.W. and J.A. Snider. 1984. Survey of the herbarium resources of Ohio. Ohio J. Sci. 84: 175-188.

- Davis, H. B. 1936. Life and work of Cyrus Guernsey Pringle. University of Vermont, Burlington.

- Elisens, W. J. 1985a. The Montana collections of Francis Duncan Kelsey. Brittonia37: 382-391.

- Elisens, W. J. 1985b. Monograph of Maurandyinae (Scrophulariaceae- Antirrhineae). Syst. Bot. Monogr. 5: 1-97.

- Eshbaugh, W.H. 1980. The Willard Sherman Turrell Herbarium. Association of Systematics Collections Newsletter 8 (6): 82.

- Eshbaugh, W.H. 1984. The role of Ohio's herbaria beyond the state.Ohio J. Sci. 84: 197-199.

- Grover, F. 1941. Mary Fisk Spencer. Madrono 6: 82-84.

- Holmgren, P. K. et al. Index Herbariorum.http://www.nybg.org/bsci/ih/ih.html.

- Lawrence, G. H. M., A. F. G. Buchheim, G. S. Daniels and H. Dolezal (eds.). 1968. Botanico-Periodicum- Huntianum. Hunt Botanical Library, Pittsburgh.

- Lenz, L. W. 1986. Marcus E. Jones: Western Geologist, Mining Engineer and Botanist. Rancho Santa Ana Botanic Garden, Claremont.

- Miller, H. A. 1968. The herbaria of Miami University (MU) and Oberlin College (OC) combined. Taxon 17: 57-60.

- Pennell, F. W. 1935. The Scrophulariaceae of eastern temperate North America. Acad. Nat. Sci. Philadelphia Monogr. 1: 1- 650.

- Stafleu, F. A. and R. S. Cowan. 1976-1988. Taxonomic Literature (Ed. 2). Vol. I-VII. Bohn, Scheltema & Holkema, Utrecht.

- Torres, A. M. 1963. Taxonomy of Zinnia. Brittonia 15: 1-25.

- Turner, B. L. 1987. Taxonomy of Carphochaete (Asteraceae- Eupatorieae). Phytologia 64: 145-162.

- Vincent, M. A. 1991. Vascular plant type specimens in the Willard Sherman Turrell Herbarium (MU), Miami University, Oxford, Ohio. Rhodora 93: 148-182.

- Vincent, M.A. 1994. William Bridge Cooke, 1908-1991. Mycologia 86: 704-711.

Policies and Strategic Plan

Visiting

Visitors are Welcome! Please make appointment with the Curator (meierga@miamioh.edu) prior to visiting. A two-week notice is appreciated for researchers and large groups to ensure the Curator has ample time to provide a tour, arrange for work space and dissecting microscopes. Please sign our guest book upon arrival.

Loans

Loans are given to Institutions (Herbaria) listed in the ‘Index Herbariorum’ (https://sweetgum.nybg.org/science/ih/) not to individuals. All loan requests are reviewed by the Curator to ensure proper guidelines are met. Send a formal loan request to the Curator (meierga@miamioh.edu) and include precise taxonomic and geographic information. In general, loan requests are made for monographic and taxonomic studies.

Gifting and Exchange

MU welcomes donations of appropriately pressed, dried, and identified materials with their labels. A digital copy of label data is appreciated but not essential. Due to space constraints, not all accepted material will be accessioned into our collections. Unlabeled and unidentified material will not be accepted. MU has several on-going exchange programs with large herbaria, please contact the Curator if you would like to set one up for your institution.

Destructive sampling

Destructive sampling is the removal of material from an Herbarium specimen for molecular analysis, SEM

studies and chemical analysis. Destructive sampling may occur only with the Curators consent. Please understand that we will make every effort to accommodate these requests but we must also balance specimen preservation with specimen use.

Executive Summary

The Willard Sherman Turrell Herbarium (MU) is the largest Herbarium collection in Ohio with approximately 640,000 North American and internationally collected specimens. In addition, to our vascular plant collection (340,000), we have large collections of bryophytes (190,000) and fungi (111,000), as well as lichen, algae, a plant-science slide collection, wood collection and North American plant fossils. We have robust historical exchange and gifting relationships with national large herbaria ensuring the breadth and depth of our collection continues to expand. MU has built a national and international reputation as a high-quality, diverse collection due to its history of international research in the Caribbean, South Pacific Islands, Africa, and South America and through its purchase of Herbarium collections from Oberlin and the University of Dayton.

The intention of our strategic plan is to provide a wholistic view of our herbarium that intentionally explores all aspects of herbarium function and organizational context. The first portion of the plan presents an overview of the collection’s assets with our vision, mission and values as well as organization and oversight. Next, we present our goals and objectives as well as strategies for accomplishing these. The subsequent assessment and evaluation of our collection address how we will measure and track our progress toward our shared goals. An environmental scan of our collection carefully outlines areas of strength and opportunities as well as weakness and threats; these are addressed in our final analysis

The main conclusions from this examination are that we must:

- Maintain our existing specimen collection with optimal curation techniques which is fundamental to all other of the herbarium’s successes;

- Expand the learning environment for undergraduate and graduate students by enabling undergraduate research, hiring student workers, diversifying graduate students educational experience with research support and teaching museum and data curation;

- Host regular and ‘fun’ University-wide outreach events to promote the purpose and benefit of herbaria to the University community;

- Provide an easily accessible database of specimens and images on our website; and

- Maintain current and develop new relationships with other national and international Herbaria by continuing our gift and exchange program and presenting at annual meetings.

Copies of the Strategic plan for the Willard Sherman Turrell Herbarium may be requested by contacting the Curator at meierga@miamioh.edu

History Botany at Miami University

Dr. Ethel Belk's talk in October 1970 to the Botany Department, Miami University, on the history of the department

Transcribed by Michael A. Vincent, January 1998. NOTE: Occasionally, I had difficulty hearing a name or word. When this happened, I inserted a blank or comment set off by brackets{}.

The tape begins with an introduction of Dr. Belk by Dr. Charles Heimsch:

"...comments Dr. Belk will make to you on the history of the department. Dr. Belk, as I mentioned to you yesterday, was here at the university from 1928, I believe (Dr. Belk interjects "9") until 1968, maybe 9, no 8, and so she personally accounts for practically all of the really significant departmental productivity, so for as students are concerned. We were speculating... I was going to do a little digging myself, with respect to the years before Dr. Belk arrived on the scene...many of the people who were products of the Botany program prior to that time have been, in one part or another, related to events at Miami since, or they would come back and visit (Dr. Belk got to know that they were local or something of this sort). A few of them gained national prominence in the botanical area, and a few (some) were graduated in the nineteen-teens, some particularly in the early 1920's. Probably the oldest one who achieved some sort of national renown was Earnest L. Stover, who was on the department at Ohio State. He graduated in 1909. Well this was shortly just shortly after Dr. Fink, the first chairman of the department, came. So sometime in the late teens or early 20's it became possible to get a degree with a major in Botany, and in this interim, there were a few people graduated in the early 20's who went into the profession, who some of you have heard of since, but probably the oldest person of greatest renown, shall we say, that most of you might know, is Paul Kramer, the plant physiologist at Duke University, who was in the class of 1926. And shortly thereafter, Dr. Belk arrived on the scene, so she's going to take it from there."

Dr. Belk begins:

"Well, I don't know exactly when the Botany Department became a botany department at Miami. I remember before there was a botany department Dr. Stephen Riggs Williams for whom the library is named had the biological science, whatever there was, on the campus. And then, Miami University opened a normal school, and at that time a department of agriculture started, and I believe that Dr. Davis was the first one in that department, and human physiology and bacteriology were associated with that department, until late in the 20's, when bacteriology became a part of the botany department, so that when I came to Miami, there was a department of Botany and Bacteriology. And the man who was head of the department at that time...

"I came in 1929; I can still remember coming in from Chicago on the train, and I wondered where Oxford was because when I got off at the station (you know where the old railroad station is?), we then had a train that had connections, and I got off at the station and I couldn't see Oxford, and the head of the department, who had been here for one year came down and got me, and had made arrangements for me to live at a house that is still standing; a house that was occupied by the then head of the department is no longer in the position that it occupied then...that lot is occupied by the Phi Delta Theta house; and I lived in a house that is next to what is now the Theta Chi house, and that was the Heckard's; Dr. Heckard was a professor in the school of education.

"But I first heard of Miami University, this isn't botany but it's my first time I ever heard of Miami University, was when I was a senior in college, and the head of the department at South Dakota State College, where I was a student, was asked to come down for an interview. He was Arthur T. Evans. Dr. Arthur T. Evans. At that time, I was a graduate assistant in the department of botany at South Dakota State College, and after he returned, we finally learned that he was going to be the new Head of the Department of Botany. I heard of it and heard of Miami University that... I'll take it back; I had heard of it once before, and that was my senior year in college. In 1928, I was getting my master's degree from South Dakota State College. Well, my senior year in college, one of my professors was a Miami University graduate, who was a classmate of the late Dr. Hughes, one-time president of Miami University, for whom Hughes Hall is named. And Mr. Cowers {? can't quite hear it} was our librarian and English teacher, and he was sending his daughter to Miami University. The first I had ever heard of it. That was two years before Dr. Evans came down for his interview, and then he came down as head of the department. I went from South Dakota State to Chicago, and Dr. Evans came to this campus a year after the death of Dr. Fink.

"To the best of my knowledge, and I haven't checked any records, I think Dr. Fink must have come about 1906, and apparently at that time, botany separated off from what was biology or the biological sciences, and a bit later, geology separated off, although the geology department began with Dr. Shideler, when he returned from getting a doctor's degree at Cornell. So the department as such goes back to very early 1900's. The only one or two of the early members who graduated from Miami with, apparently, majors in Botany, were Dr. Stover and a man who's still living (Dr. Stover is no longer living), and a Vernon Landis. Now Mr. Landis was a member of the department later; I'll come to him again; but he and Dr. Stover were two of the early graduates (1909, I think). So there were, the department was very small. As far as I know, at that time, they had only...Dr. Fink taught all of the botany. When it enlarged, to more than assistants must have been in the 20's. And at that time, Dr. Fink and an instructor, I believe, taught the botany. The man who carried on after Dr. Fink's sudden death (he died of a heart attack in the building), and his work was carried on by Miss Joyce Hedrick and Mr. Lohman. They were doing the botany when Dr. Evans came down, and they continued as instructors the next year, when Dr. Evans asked me to come down for a couple of years. I said well, I'd come for a year or two. {Laughter} I had ideas then of going right on to finish graduate school; well, things happen sometimes. Well, the botany...at that time, the enrollment was larger than it had ever been...we had four sections of botany.

"Now, the year before I came, and up to the that time, which was 1928/9, the first semester of the year 1928/9, botany moved from Brice Hall. Those of you who have been on the campus know where the remains of Brice Hall is. And up to that time, which was at the end of the first semester, or maybe it was Christmas vacation of 1928, Botany and Physics moved out of Brice Hall into the south wing of Irvin Hall. Physics had the first two floors of that wing, and Botany & Bacteriology had the top floor of that wing. So I missed the original Botany Department by one semester. The staff at that time (1929) consisted of three full-time people and one graduate assistant. Two of us were new in 1929, and one, Dr. Evans, the head of the department, had been there only one year, so there was no real continuity, you see. That's why I know so little about what went on before 1928.

"Dr. Stark taught bacteriology. He came in the same time I did, and also was scheduled to teach, when it was offered, plant physiology and plant pathology, and also, if necessary, to take a section of freshman botany. I came, and Dr. Evans asked me to teach morphology. So I had morphology and freshman botany, and Dr. Evans had a course in ecology, and freshman botany; he gave the general lectures. Up to the time that Dr. Evans came, botany had been a laboratory science, really laboratory. Laboratory periods were three hours long, and most of the general elementary botany was drawing. I know two women on campus, both Phi {?Betas}, who are the widows of former members of the faculty here at Miami, who lived through botany when they had to sit and draw for three hours. {Laughter} One other person who lived through that with Dr. Fink and who since has been a very important member in Arts & Sciences is Miss Kathleen Kuhlman; she was in the last class that Dr. Fink taught {voice drops off}... But they hated it! They hated botany. I know another former member of the faculty here who was a contemporary of mine (she's no longer on campus), who would have liked to take botany, but she couldn't draw well enough, and so she didn't think she'd make an "A", therefore she took geology and made an "A" and Phi Beta Kappa. I guess she thought perhaps her lack of skill with a pencil would have been a difficult thing in botany.

"Well, when we came to the campus, Dr. Evans had already then by that time shortened the laboratory period to two hours, so that elementary botany at that time consisted of three two-hour periods and two one-hour lectures. And in botany, the first thing that we did, in the fall, this was my introduction to botany at Miami, was to take the first class trip to a market garden that was on the edge of Oxford out beyond the railroad tracks, to show them vegetables growing. The place now is occupied by the Headley {voice drops off}.

"1930, that year, 1929-30, the graduate assistant was a man from Nova Scotia, Iverness Crowell; he did get his master's degree that year. And the next year, you probably recall, there was a stock market crash in '29, we had a graduate assistant for a year, and then funds were cut off, and so he was here for only a short time; this was Mark {cannot hear last name}. Dr. Evans and Dr. Stark and I continued as the Botany and Bacteriology Department until I left to go on leave of absence for advanced work in 1935. There was one interval in which there was a difficult period in the fall of '30; I had an emergency appendectomy with complications and was out for that year, so for a semester a Mr. Klinger, who had worked with the Starks at the {name?} Laboratory in Colorado came in for a semester. Then until 1935, we continued with the course as we could do it, In the meantime, however, I had inherited taxonomy, because taxonomy had then become just taxonomy of vascular plants. When we first came, taxonomy had included everything, and all courses were year courses, there were no semester courses at that time. Then there became semester courses were inaugurated sometime during that period. So I inherited taxonomy and taught that.

"In 1935, and this Dr. Heimsch can account for, Dr. Snell, who had just gotten a doctor's degree at Cornell University, came to Miami, but he stayed only one year. I had gone for a two years leave and at the end of the first year, Dr. Snell had an opportunity to go to the University of Utah, because Bassett Maguire, who was at Utah, and is now connected with the New York Botanic Garden, came back to Cornell to get his doctor's degree, so Snell went to Utah. Then, to Miami came a man who had some experience as a University of Indiana graduate, had been a graduate assistant at the University of New Mexico, by the name of Stanley (Stan) Brooks. I had expected to come back after two years, and it turned out that I was asked to stay an extra year, and Brooks stayed then two years. And those of you who have had any experience with the herbarium will come across perhaps, some specimens labeled "Brooks, Howard, Barghoorn, and Lunsford". He was a bachelor, and he would take these three boys, who were then majors in Botany. Howard had been a freshman my last..in '35. And they would go off on collecting trips. So that accounts for the herbarium specimens labeled "Brooks, Barghoorn, Howard, and Lunsford." Barghoorn and Howard went on as botanists, then Lunsford became, I suppose you might say, a chemical engineer; he had done quite a lot of work in chemistry when World War II intervened.

"In 1938, when I came back, Botany I (Elementary Botany), had changed again, and this time, it was being taught with three one-hour lectures, and one three-hour laboratory. I think this influence perhaps began with Snell, because at Cornell, botany was taught with two one-hour lectures, and one two-and-a-half hour laboratory. However, it was to my way of thinking, not very satisfactory. Dr. Evans gave the lectures, and the rest of us, in addition to the other courses we taught, had the laboratories. When it came to examinations, the questions always were (the students would ask), 'Is it going to be over the lecture, or is it going to be over the lab?' They didn't have the idea that is was one course, it was two completely separate things, I think, to their way of thinking. And so, I was..., and I talked it over with Dr. Stark, neither of us were very satisfied with it, and considered a possible change in the organization of the course.

"However, before that came about, we had an interruption of sorts, and it continued, and that was World War II. Before that, we had right up to that time, the department had expanded, that is, there were enough students, because, when I came in 1929, Miami University reached 2,000 for the first time in its history. I can't remember how many there were in 1940/41, but it was over 3,000, and I think perhaps around 3,600. {Dr. Heimsch interjects that it was 3,000 in 1936.} 3,000 in '36. I don't think it was as much as 4,000 in '41, but we had an addition to the department, this addition was Dr. William Gray, and he came in the fall of 1940. He taught physiology. By this time, bacteriology had expanded, and there had been a request for a course in community hygiene that Dr. Stark taught, also addition in bacteriology for {word?} students, plus the regular bacteriology had expanded to include pathogenesis.

"Now all of this still took place up there on the top floor of the south wing of Irvin Hall {Dr. Belk said Upham Hall}. There was one laboratory, which ran the length of the wing-- not the length--the width. The tables were V-shaped, very narrow at one end, very wide at the other, and were fitted against windows; that was all the light that we had. There were four of those enormous tables in that laboratory, and all of the elementary botany was taught in that one laboratory. There was one laboratory which was the bacteriology laboratory, and there was one additional laboratory, so-called; this was the room at the top of the back stairs, and that room had to include the taxonomy, the plant physiology, and pathology and so on, and later, dendrology and, what else did we have in that...ecology, and microtechnique, and it was the herbarium.

"You may remember, Dr. Heimsch, when we finally got the herbarium cases all in one place, because there were some in the elementary laboratory, there were some in the entry to the little cubby-hole I had as an office, there were some in the office of the head of the department, and there were some back in that laboratory. We finally got them all in one place by using rollers and student help; I think Dr. Heimsch put a shoulder to some of those cases. The herbarium, up to that point, had been a very small herbarium, of vascular plants. There was one full case of fungi. These were the remains of the Fink collection, because the private collection of Dr. Fink, the lichen collection, was sold to the University of Michigan, and accompanied by Miss Hedrick, who was an instructor when Dr. Evans first came here. She went with the herbarium to finish a book that Dr. Fink had been writing on lichens, and is now Mrs. Jones, is that right?

"Well, up to World War II then, or two years prior to it, it was still Botany/Bacteriology, and an additional {word?} for Dr. Gray. Well, World War II hit us hard. Dr. Gray went back to research. He came from Seagrams and went back to Seagrams. Finished out the year '41/'42. And of course by that time, many, many of the young men had left, and they were already bringing in, beginning to bring in that fall, students who were concerned in being trained...they were actually armed forces...they brought in two temps, a naval radio training school. And anyone who was at all skilled in code was pressed into service and teaching in the naval radio training school. And some who had no skills, but who acquired them during that time were also assigned to the radio school. So, from 1942-3 until they began to phase out the radio school, the Botany Department shrank considerably.

"In the fall of '43, Dr. Evans, still head of the department, was ill and I was teaching in the naval radio training school. But Dr. Evans said he would be back in two or three weeks, and so until then, he would ask Mrs. Stark to carry on, expecting to be, as I said, back in two or three weeks. Mrs. Stark had her master's degree from the University of Illinois; she was a graduate of the University of Chicago, where she had botany with Coulter, in Illinois {cannot hear words}, had taught before she was married in a college in the east, so she was totally capable of carrying on. But Dr. Evans did not recover, dies in the fall of '43, and I fully expected to be called back to the Botany Department. However, the president was then Upham, after whom this building was named, and when I had no word from him, I went to see him, and said "Shouldn't I be going back to the Botany Department?' He said, 'No! I can get somebody to do Botany.' But he couldn't get anybody to do the radio. So I continued in the radio school, and Mrs. Stark had the whole year in Botany, aided by a young woman who was at Western College, because by this time a course called Economic Botany had been added, and that was Miss Jean Hendrix. Although I didn't know it then, she was the future present Mrs. Cobbe. So Miss Hendrix supplemented and taught one of the laboratories in Elementary Botany and taught Economic Botany. Mrs. Stark did the lectures for the rest of it, and Dr. Stark was teaching bacteriology, although in the summers he also taught in the radio school. Then World War II ending..well, in the mean time, there was a search going on for another head of the department. This was finally settled with Dr. J. Fisher Stanfield coming in the fall of '44.

"In the mean time, Dr. Stark and Mrs. Stark and I had talked about the Elementary Botany and we talked to President Upham, and I remember saying that I think we can do a better job and get more accomplished by taking those same 6 hours that the students are having now (3 one-hour lectures and one three-hour laboratory), and using them in a different pattern by teaching three two-hour sections. That was the... Dr. Upham said "If you think you can do a better job and accomplish more, then go ahead and try it," and so we did. This was when Dr. Stanfield first came, and so at that time we were teaching botany for the first time with three two-hour sections (same credit you see, same 6 hours). The other courses were not changed. Then, that year, and this is one name I can't remember, a man who had been a colleague of Dr. Stanfield's at {name?} Teacher's College in Chicago was here for one year, this year of '44/'45. He taught in Zoology, he taught some bacteriology, he also had a section of botany; what his name is...I can see him, but I couldn't remember that name, and I didn't look it up.

"Then, the next year we were faced with the post-war influx, and the further expansion of the department to take care of returnings, and so an addition was made to the department. That year, Dr. Genevieve King became full-time in the Botany Department, and she was full-time botany, replacing the man who went back to Chicago, who had not been a full-time member of the Botany Department. But even that wasn't enough, so we had to have more help, and people were very greatly in demand, trained people, because there had been so few during World War II. And I remember Dr. Stanfield saying 'Now isn't there someone of your graduates who might be returning who could come in.' Well, I went down the list of the ones who might possibly be in the area; one had been working doing war work with Monsanto, but he was then on his... getting his doctor's degree. So I happened to think of another one whose home had been in Cincinnati. I knew he was back; he was a very good student; he was in the class of '42. They allowed these men who were seniors to finish out {here the first side of the tape ends}...

"...and so he was in that class of '42, along with Canright, {?name}, {?name}. He had been in the service, and I didn't know his address. So Dr. Stanfield said 'Well, go to Cincinnati, and see what you can find in Cincinnati.' I looked up the address given in the registrar's office for William Kline, but when I got to Cincinnati, in the city directory there wasn't any William Kline at that address. So I changed fifty cents into, I guess it was nickels, and I started in the directory calling the "Klines" of Cincinnati. {Laughter} And finally, I got one...I'd say 'Is this the home of a student of Miami University William Kline, who graduated...' and so on, and then they'd say 'No.'. Well, I finally got one who said 'Well, who wants to know?' And so I started to explain, and it was Bill Kline's mother that I got. So, I left word for him to call that evening if he were interested, and would come. He had been a student undergraduate laboratory assistant for two years as an undergraduate, and he called that evening. I explained the situation to him, and he said 'Yes, I would be interested.' So, he came up to see Dr. Stanfield, and then came that one year. So, that year, which was prior to Dr. Wilson's arrival on the campus, we had Elementary Botany with Dr. King, Mr. Kline, Dr. Stanfield, and myself. So you see, the Botany Department has now expanded to four members; bacteriology still a part of it, had, I would say, still one member, although during that period, Mrs. Stark was a part-time instructor, taught the Elementary Botany course, and also assisted in bacteriology.

"Well, the facilities hadn't expanded; even though we had increased the staff, we still had the same number of classrooms or laboratories, which were these two laboratories that I told you about, and we had added another pair of courses. There had been quite a number of requests that we give a course in woody plants. Dr. Hefner had talked to me about taxonomy, and he wanted a number of his majors to have taxonomy, but he didn't want them to have to take Elementary Botany if they'd had elementary zoology. So we reached some sort of an agreement that people who had Elementary Botany might be able to take entomology, and that people who'd had elementary zoology might be able to take Taxonomy. There weren't too many who did that, but there were a number of requests for a course in woody plants. We had always, after the vegetables I told you about earlier, the next thing we did was trees; we had done that and continued to do it. Then the courses that were created were anatomy, and dendrology; against my recommendations, the course was called Dendrology; I called it Trees and Shrubs, because I thought if that was a good enough name for a course in woody plants at Cornell, it would be good enough for a name at Miami, but the Powers Beyond (the curriculum committee) decided that if they had a course 'Dendrology' at Oberlin College, it should be called Dendrology at Miami University. So, it was.

"The course in anatomy, I fully expected to...having written the whatever you call it...prospectus for both of these...the new person who was coming in that fall would be presumed to take the dendrology, and I would have the anatomy; my major area field had been morphology and anatomy; I had worked with Dr. Eames at Cornell. And the new person was Dr. Genevieve King. She said she wouldn't do it. She didn't know where things were around here, and she would take the anatomy, but I must take the dendrology. So, this is what happened, and as a matter of fact, I never did get to teach anatomy, because Dr. King had expected to return, but got a very good opportunity to go to Morehead State College (now--it was then State Teachers College of Minnesota), and left, and we were very fortunate to have Dr. Wilson.

"By this time, Dr. Stanfield was working on trying to get a lecture room, which was between the office of the head of the department and the one laboratory for Elementary Botany, converted to a laboratory. It took a good bit of doing, but eventually, I think in '48, didn't we get it? In the mean time, there was a room across the hall which had a darkroom, and which had the only refrigerator, to serve both botany and bacteriology (mostly bacteriology). It had two desks. This was where Bill Kline and Genevieve King had their "office", and where Professor Wilson had his "office". The mimeograph machine, the coffee, and so on, was always in there...how we ever lived through that, I don't know... But, then we did add, and this next room was converted into a laboratory, and in the meantime they were working on this lovely wing of Upham, which was vacated when we moved over here.

"So in the meantime, we had an instructor. After Mr. Kline was here only one year, and went on to Purdue then to pursue his graduate work. The man was a graduate of Miami University, in the class of 1909, a contemporary of Dr. Stover's, and one of the early graduates of Dr. Fink, who had retired someplace in the west. And living on a farm out in the Gratis area, helped out by teaching here as an instructor, and continued for three years. This was Mr. Vernon Landis. And he had graduated in 1909, went to the University of Cincinnati, met his wife, who was a classmate of Dr. E. Lucy Braun's; they both graduate the same year. Then there was a regulation that an instructor could be reappointed only for three years, unless there was very good evidence you could keep going beyond that, and for three years if you were not going on for graduate work.

"So, Mr. Landis's three years were up and the replacement, I suppose you might say, or the additional member of the department came in from Michigan State, actually graduated in forestry with a master's degree. And this was Richard Fox, and he stayed two years--a year and something. He was with us still when we moved over to the wing of Upham. Incidentally, Carmen Cosa, because he would always talk football with the boys, Carmen Cosa took Elementary Botany with Mr. Fox. {Dr. Heimsch interjects something here about the football comment, but it is too faint to hear.} Yes. So when Michigan State would win a game, someone would put on the bulletin board a full-page spread about what Michigan State had done in football, and they'd have a big discussion about it. But he had an opportunity to go back to Michigan as a forest entomologist, an opportunity which was too good to be turned down, and so there was the problem of a replacement for him, if he could get a replacement, then the dean was willing to release him, otherwise the dean was not interested in releasing him, because school had started, you see.

"One of our graduates, a World War II veteran, who had done very well, and was a major, had gotten his master's degree at Syracuse University. Because of the fact that by this time, Miami was interested in a pre-forestry program, Dr. Stanfield thought it a propos that an instructor have some background in forestry. This was Edgar Ekkes, one of our graduates, and he was at that time free. Dr. Stanfield wrote him asking if there were some of his colleagues who would be interested, and he wrote back that he would be interested. And you remember when Ed came and was quite interested in doing it, so he was a replacement then for Fox, so Fox was here only a very short time.

"This then was the department in 1951, 2, 3; we went up to about '54 with Ekkes. But he was not going on, so after his third year, he left, and the man who replaced him was Ben Graham, a colleague who is still at Grinnell, I think. He came to us from Duke University. So here, now, the department...In the meantime, I've not mentioned the fact that bacteriology separated from the Department of Botany, for a time was attached to Chemistry and became an independent Department of Bacteriology with Dr. Stark as head, so Botany now is without additions of bacteriology, and this took place while Stanfield was here. Graham stayed two years, and was replaced by Harvey Miller. Dr. Miller was here when some of you came...Dr. Cobbe came...

"By this time, Miami has now been growing and growing and growing, and we were able to add another member of the department. So the next addition to the department was Dr. Cobbe. Now the department consisted of Dr. Stanfield, Dr. Wilson, Dr. Miller, Dr. Cobbe, me...five people in the department, all botanists, plus, I think, two graduate assistants. But during these years, '56, Dr. Stanfield lost his wife, and then he himself was ill during the second semester, and we carried on without extra help...'57...'58... Dr. Stanfield passed away, and again without additional help, we split up the load and carried on, with the help of Dr. Noggle, Dr. Ray Noggle, who was then at the Kettering Foundation, and he, because none of us could absorb the plant physiology, Dr. Noggle came down on Saturdays, and so the plant physiology continued with his supervision, and help and assistance for that year. So we finished out the year, and were fortunate enough in the spring of '58, to have appointed as head of the department, Dr. Heimsch.

"Immediately, he was granted a year's leave of absence, so we were faced again with a situation in which we had to have a temporary person. On a one-year appointment, Dr. Richard Smith came, and then in the fall of 1959, Dr. Heimsch was able to come to us. From 1959 on, it's current enough...

"Any questions any of you would like to ask? Now, I haven't mentioned people who went through, and there are all kinds of interesting things that happened with the students. One of the things I think that was most interesting about Dr. Evans, and the only one here who knew Dr. Evans is Dr. Heimsch, and that was his unbounding enthusiasm. He would always say 'Well, there's just no doubt about it, you can do it.' And he expected you to do it, and he just took it for granted that you would do it. And I think that this rubbed off, and people did more, many times, than they thought themselves, that is, they played over their heads, in some cases; maybe not, maybe they played up to their capacities.

"And I well remember, now this goes back prior to my time at Miami, because this is a name that some of you will recognize, and that is, Dr. Cheadle, who is the chancellor now of Santa Barbara, was a South Dakota boy, and I knew him before I came to Miami, because he was a freshman at South Dakota State the year that was finishing my master's degree there. His brother was a sophomore. They came from a town about three times the size of my home town, by the name of Salem, South Dakota. They were outstanding basketball players, because while these brothers were playing, they had won the state tournament two years in succession. Well, the older brother came to South Dakota State, and told his younger brother 'You won't have any trouble up there. I can get...' We had a grade system where 'M' was equivalent to a 'C'...and then we had an 'S', which was superior, and 'E' was excellent...those were the two grades above, which would be equivalent to 'B's' and 'A's'. He said, 'I and get C's and you can get C's and B's...' He came in as a freshman, and Dr. Evans hired him, having heard about him, of course, and having been interested in basketball, he hired him as the dishwasher for the department {sqeaking chair obscures words here}.

And when he was in South Dakota, the department was very small; it consisted of Dr. Evans and three graduate assistants, of which I was one, and any students who were interested at all were welcome to come in. The office was a sort of a corridor type of office, because you had to go through the office to the herbarium, and from the herbarium you went into the storage room, which was where I had a table. So, these boys, Cheadle and a couple of others who would come up to wash dishes, would be around the department when there were classes going on, and Dr. Evans was interested in what he was doing. He would say, 'What do you mean, you let him get an 'A' on a theme and you only got a 'B'? Well, come on, boy, just snap out of it! You're not going to let him show you up, are you?' And he would give them a pep talk, and he would do this with other undergraduate students, indicating that he was interested not only in the fact that they do a good job in botany, that was taken for granted, but they weren't going to show up as lame ducks in other departments! So, if they were taking other courses... 'Chemistry?...well, come on now, you show what you can do in chemistry.' In this way, he would keep needling, and students would respond; as a matter of fact, a number of students mentioned, and I remember, recall very distinctly that Dr. Cheadle said to me (this was many, many, many years later), he said, 'You know, I'll never know how that thing Dr. Evans did when I was a freshman had to do with my success.' He was a Phi Beta from here, of course. He said, 'I think I got an influx of courage...I could have gone along, just getting 'C's'; if nobody paid very much attention, what difference would it make?' And, he was convinced that it had had an impetus which carried on through his career. He is one of our outstanding graduates, and he played football, basketball, and was a wing man in track, so that was quite an accomplishment for him, and it's shared by all the department; Junior Phi Beta Kappa, and to take part in all the sports he did, in addition to earning their way through college. One of the things that South Dakota did not forgive Dr. Evans for was persuading the two Cheadle brothers to leave South Dakota State {laughter}, and come to Miami.

Nobody had much money in South Dakota. The Depression began there in 1925, '26, because banks started closing in '26 up there, so everybody worked, and more people worked there way through college; maybe not more, but more of the people I knew personally were working. And at the time he and I came, he used to fire furnaces. He had his route, which he would make to fire furnaces, and one of them was Dr. {could not hear name}.

"During the '30's, we had as a supplement, we started out as...became...MIA. Now those were the people who were assigned to a department as assistants, were people who would not be in college, or who would have to drop out of college because of finances, so it was possible to get some things done. Now they could not be used for ordinary departmental work. It had to be something supplementary, supposedly creative, to which they were assigned. Well, something that was not part of the departmental schedule was getting plants mounted for the herbarium, so we had one girl do that, and we had another one who made slides. This was Irene Bucholtz, and a very excellent technician; she had developed in the early course in microtechnique. Because, the very first course in microtechnique, Dr. Evans taught, then he handed it over to me, so I was teaching that; there was no anatomy, what anatomy there was was in microtechnique.

"But I recall the first summer that I was here, I had four people take microtechnique, three men, and a woman, all of whom...no, one man did not get his master's degree; two of them did, in botany. The woman had a minor in botany, and a major in English, later went on to get her Ph.D. in English at the University if Cincinnati. But it was the first time I come across in microtechnique someone who was red-green color-blind, and we were using as stains safranin and light green, and I didn't know it until the course was half over, and it was only five weeks! But, the fall course in technique was only three, and interestingly enough, they were all three the same last name, which was Lang, and one of whom turned out to be a very, very excellent technician, although he is no longer a plant chemist, and that is Dr. Andrew Lang. Dr. Lang was the first botany-chemistry major we ever had at Miami University, and he went on to become a consultant.

"But, Dr. Evans would have a picnic or a gathering at the drop of a hat...he would just collect people and say, 'Come on out for breakfast, and I'll make the pancakes.' And so he would this, they weren't just students that came. He would have maybe a dozen of them out there Sunday morning breakfast; Mrs. Evans was a very understanding and patient person. She would say, 'It really would be easier if Art would let me make the waffles, but he enjoys it so...' And he did.

"During the time that Dr. Gray was here, we had visits from a couple, and Dr. Evans decided we should have a winter picnic. The couple of visitors that year were Dr. Fuller, and Ray Noggle, who was one of our graduates, actually not a botany major, but he was in the botany department at the University of Illinois. His comments on how he came into botany is interesting itself... But, they came over. Dr. Noggle was going on to his home in Dayton, and Dr. Fuller stayed with the Evans'. So, our winter picnic consisted of waffles, and sausage, and hot maple syrup, because at Hueston Woods, which was still then the Hueston farm, the sugar cabin was running, and they were making maple syrup. And there was a little adjoining room where there was a round pot-bellied stove like the one they used to have in the cabin for fishing, that you could cook on top. There was a big old electric light bulb, so you could connect something in that, and Dr. Fuller, and the Grays, and the Evanses, and I (Dr. Stark was unable to come), went out for a winter picnic.

"So, I think, if anything, the students, as undergraduates...Dr. Evans was always talking to them where ever he happened to see them...got the feeling that they were people and we were people; we were not only professors or teachers, we were people; we were all people. I think this went on continually. Dr. Wilson was sort of snowed under when we'd have coffee, although then it was really limited to seminar, I think the coffee began when I had brought a coffee pot and had a hot plate. I had a graduate assistant in the 8:00 Elementary Botany class, George Hagin, who was from Minnesota, and about a quarter to ten, I'd say, 'George...', and George would go down in and plug in the hot plate (this wasn't an electric percolator), so that at 10:00 we could have a cup of coffee.

"The students who came over when we moved over to that wing of Upham Hall, were all very, very good friends. We had a fine group of undergraduate students at that time, and graduate students, too. But, it was just as well, because we had to make do, again, with temporary equipment. There had been a strike, so none of the furniture was in. The floor plugs were standing where there were to be desks. The botany, then, was taught with temporary tables, and they were the mess tables that were left from the navy radio training school that were stored down in a temporary building next to Fisher Hall. They were wood, but Dr. Evans and Dr. Wilson and Mr. Fox (I didn't do it), sanded these tables off, and smoothed them off so that they could be used in Elementary Botany. And then we had other temporary tables which were used for microtechnique and the other areas, so we limped along for, well, most of that year. They worked on them some during Christmas vacation...we still went most of that year with temporary tables, but people were very good-natured. What was the herbarium was a large room, and areas for preparation were small.

"Soon after we moved over into that wing, Korea came along. So, returnees from Korea...well, it just became a PX, and was a PX for as long as we were over there.

"For a number of years, there was no such thing as a staff meeting. If Dr. Evans was in a mood to talk about things, he'd say, 'Just call Stark, lets talk to him about this.' That was a meeting, you see; there were only the three of us. It's remarkable...we've had some outstanding people. With some of them I used to say, 'Be sure now to take this course when you get to graduate school.' And I remember stopping at the University of Iowa, in 1934; I went out to a meeting, a symposium, which was at Ames. Dr. Stark drove, and Dr. Evans didn't go. But we stopped at the University of Iowa, where we had two graduate students, Irene Bucholtz and William Hughey, and went on to Ames, where Dr. Hughes was then President. This was Farm and Home Week, and they had quite an outstanding program, and one of the highlights of the program in last week was the awarding of an honorary doctor's degree to the then Secretary of Agriculture {name?}, who was an Ames graduate. At the meeting, at dinner, Dr. Martin, who was professor at the University of Iowa (I met him because Hughey had introduced us), lowered his glasses, and said, 'Hmm, so you're responsible for the morphology Hughey knows.' No, I was responsible for what he didn't know. And that's what I always felt about the students who went off ..."

{The tape ends here.}

Contact the Herbarium

Physical Address:

Upham Hall 79100 Bishop Circle

Miami University

Oxford, Ohio

Mailing Address:

212 Pearson Hall

700 High St.

Miami University

Oxford, Ohio 45056

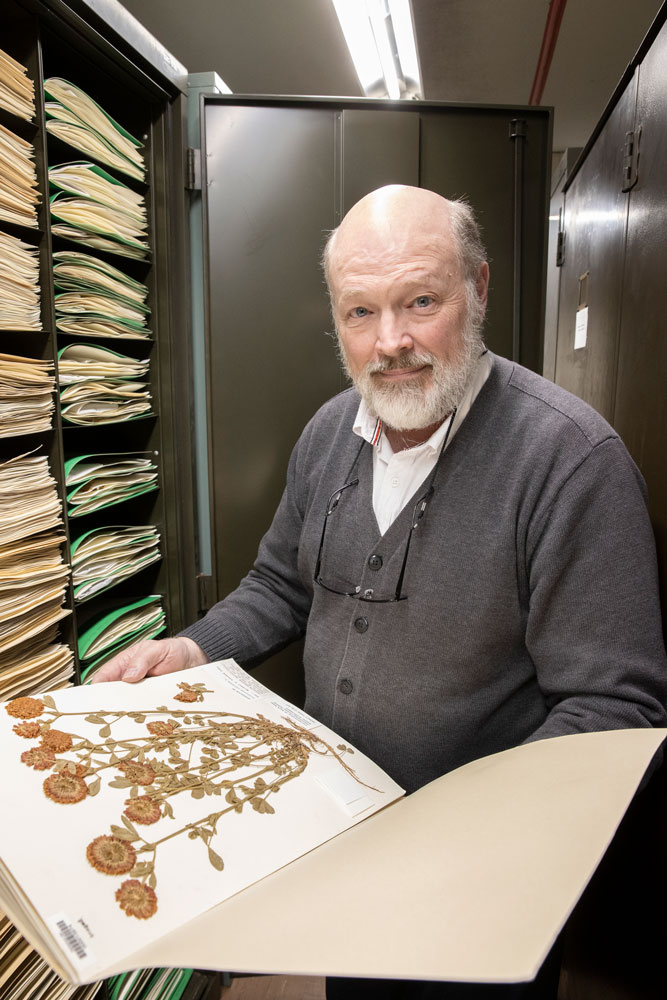

Emeritus Curator, Michael Vincent, Ph.D.

Emeritus Curator, Michael Vincent, Ph.D.