History's Lost and Found: The Story of Jerry Williams

A scholar's research and a nearly 80-year old letter exposed and righted a forgotten wrong

By Vince Frieden, strategic communications coordinator, University Libraries

Within a yellowed manila folder, filed amongst the endless rows of vertical files and tidy blue boxes containing Miami University’s history, waited a heart-wrenching story in need of a voice.

It spoke of a time 25 years before the eloquently stated dream of Dr. Martin Luther King Jr., and it contained a now unthinkable wrong – long overdue for correction.

A story finds its storyteller

When Zeb Baker first visited Miami University’s campus to interview for a job in the University Honors Program, he had a research project going on the side.

The son of a former Georgia Southern University athletic director, Baker was fascinated by the history of segregation in college football and was in the early stages of researching his upcoming book, “Playing the Game of Segregation: Race and College Football in the Postwar Midwest.”

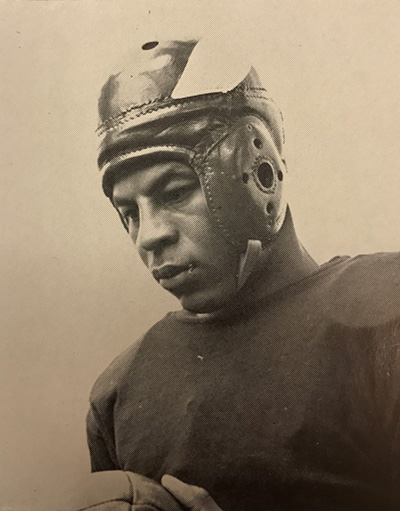

Williams was a two-sport student-athlete. (Photo from University Archives.)

As part of his visit, Baker stopped by the university’s archival collections, then located in Withrow Court. During the visit, then-university archivist Robert Schmidt offered a folder of materials about African-American students at Miami, hinting that Baker might find something of interest.

It included a pair of 1939 letters regarding an African-American student named Jerry Williams.

The exchange between Miami’s then-president Alfred H. Upham and an assistant superintendent of schools from Cleveland came at a time when Miami’s enrollment of 2,700 included only 15 African-Americans. In those days, African-American students did not receive housing in the residence halls and received meal service out the back doors of local restaurants.

It was also a time when student teaching in Oxford schools was not an easy option for an African-American.

The letter discussed Williams’ qualifications for certification as a teacher. President Upham spoke glowingly of the respect Williams had earned from his classmates and faculty while indicating he had completed all required course work. However, the university could not confer a degree because Williams had not completed the required practice teaching – an opportunity unavailable to him because of his race.

By today’s standards, some of the language and inferences in the letter are outright offensive.

In his response, the clearly frustrated assistant superintendent openly questioned why a university would admit a student into a school of education without being obligated to provide practice teaching. He conceded, however; that without the required degree and teaching certificate, he could not permit Williams to teach.

“I was flabbergasted,” Baker said. “Having researched in some 190 different archives, I can authoritatively attest that I had never seen anything like the exchange between these two men.”

Uncovering a lost Miami legend

Baker, now a senior associate director of Miami’s University Honors program, got the job and soon thereafter began pulling at the threads.

“I came to find that, in many ways, Jerry Williams was probably the most famous student at Miami during that period,” Baker said. “He was incredibly well admired by other students.”

Williams, considered Miami’s first African-American football standout, was a two-sport student-athlete, earning three letters each in football and track & field. A two-time All-Buckeye Conference back, he also was the place kicker for the 1936 Buckeye Conference champions. On the track, he helped lead Miami to three conference titles.

Jacqueline Johnson, the current university archivist who succeeded Schmidt, became an ally in the effort to uncover Williams’ story.

From the original letter, they knew Williams had attempted to gain practice teaching by assisting in the instruction of an automobile course at Miami. Through another uncovered letter, they learned that Williams received National Youth Administration aid and worked in the Withrow Court athletics equipment room.

They already knew he had to be an excellent student to earn acceptance into Miami as an African-American during that time. Along the way, they discovered that Williams ran a leg of a state championship relay at Cleveland’s East Technical High School with the legendary Jesse Owens. The search also turned up Williams’ 1999 obituary.

“Historical research can be deeply personal work,” Johnson said. “You often find yourself immersed in another’s life. It’s powerful and sometimes life-changing.”

The Williams family receives their father's degree in 2017. (Photo by Zeb Baker.)

“A great day”

From that point forward, there was never any hesitation about what needed to happen.

After verifying and re-verifying with the registrar that Williams had indeed completed all his required coursework, the conversation elevated to the president’s office, the provost’s office and to Michael Dantley, dean of the College of Education, Health, and Society.

In April 2017, Dantley placed a phone call to Janis Williams (Miami ’68), daughter of Jerry Williams. He explained the situation and informed her that her father would receive his Miami University degree, posthumously, at the college’s spring commencement activities.

“I burst into tears right away,” Janis recalled.

Dantley presented the degree to the family during commencement activities on May 14, 2017. He introduced Williams’ story by announcing it was time to right a wrong.

“Jerry Williams’ story is a reminder that there is still a lot of work to do when it comes to making our world a more just and equal place,” Dantley said.

Between conversations with Williams’ family and a treasure trove of documents hidden away in the family’s attic, since donated to Miami’s archival collections, the life story of an accomplished but deeply humble man emerged.

After another attempt at gaining professional teaching experience failed, World War II arrived, and Williams enlisted. He served as a master sergeant mechanic with the famed Tuskegee Airmen.

He left the military in 1947 and balanced two jobs for much of his life.

"He'd leave at 6:30 in the morning, teach all day, then work the 3-11 p.m. shift with the police department," Janis said. "I don't know how he did it, but he always had time for us."

While records and family recollections fail to tell the story of how Williams finally earned his way into the classroom, he worked as a teacher at Central High School and Robert H. Jamison, Nathan Hale and Audubon junior high schools until his 1979 retirement. He also spent 25 years as an investigator with the Cleveland Police Department, working for a groundbreaking juvenile division.

Jerry Williams

“He was a dignified man, a good husband and a great father,” Janis said. “He was a man who never boasted about his accomplishments.”

Despite the wrong that Miami did not correct in his lifetime, Williams never voiced animosity toward the university. Until Dean Dantley’s phone call, Williams’ children, Janis and Jerry Jr., never knew why their father did not graduate.

“He always spoke about how beautiful it was and about this feeling – Miami just had this feeling,” Janis recalled.

Now on display, in the room where Williams used to sleep, are a Miami University degree and a Miami flag, presented to the family by President Greg and Renate Crawford, which flew over Miami’s campus in Williams’ honor. In fall 2017, Williams received another honor when he took his rightful place in Miami University’s Athletic Hall of Fame.

“I know how much Miami meant to dad. He loved this school, and he imparted that to us,” Janis said. “That’s why I was so emotional when Dean Dantley called. I thought, ‘You finally got it. And you deserved it.’”

The story of Jerry Williams (Miami ’39) – a tale of redemption that might never have been if not for a nearly 80-year old letter that opened the door to the shining example of a remarkable Miami man.