Mission: Design a fun, more engaging therapeutic hand cycle for children with cerebral palsy - in four weeks

by Margo Kissell, university news and communications

From a young age, many children with the neuromuscular condition cerebral palsy do physical therapy to improve their strength, coordination and range of motion.

But children who have difficulty focusing for an extended period of time can easily become bored with their therapeutic regimen.

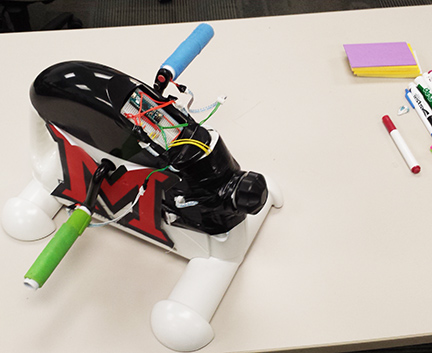

The students' final prototype consisted of a small, modified hand cycle outfitted with motion and force sensors.

Enter Michael Bailey-Van Kuren and his Miami University engineering students, who spent four weeks in London this summer on a mission to design an engaging but inexpensive therapeutic hand cycle connected to a custom video game.

"Pediatric therapy is about play," said Bailey-Van Kuren, the C. Michael Armstrong Professor of Engineering and Interactive Media and associate professor of mechanical and manufacturing engineering. The students' primary goals were to modify a device to make it more fun so young patients will focus longer and want to pedal longer and enable it to collect data showing how the children performed in therapy.

Miami students have worked with private therapy clinics here and abroad on solutions to increase motivation for therapy since the 2013-2014 school year.

The most recent effort came in June when 14 Miami students traveled with Bailey-Van Kuren to England as part of Miami's London Interactive Design program. The 14 students split into three teams, each working on a different project with the Birkdale Neuro Rehabilitation Centre.

Five engineering students — Eric Lee, Xuan Cao, Tori Delap, Matt Serio and Jiayi Zhai — worked on the hand cycle design after gathering input from the clinic's director.

Farshideh Bondarenko, the Birkdale clinic's director and a neuro physiotherapist, said via email she was excited to work with the Miami students because "very rarely" do therapists have input into the design of tools they could use to assist with treatment.

Miami students participating in this summer's London Interactive Design pose with Farshideh Bondarenko, director of the Birkdale Neuro Rehabilitation Centre.

"I was not going to miss this opportunity, as I really needed to have a bike which is not expensive and can be used at home and is not occupying a big space in someone's sitting room," she said.

Bondarenko called her request "a tall order," but for Bailey-Van Kuren, it was another opportunity to show his students how engineering can be used to improve a situation to help people in the community.

"I got exposed to this area because I have a son with special needs. He's now 14," he said. "Really, I started seeing project ideas 14 years ago right off the bat."

Team project manager Eric Lee, a senior mechanical engineering major with a co-major in premedical studies, said knowing that success with their design could mean success for the patient was a huge motivating factor to do their best.

Working long days toward a goal

Lee said the four-week turnaround was hard because they only had time to build a rough prototype. "However, we were completely immersed in the culture and the project, allowing us to fully focus on the task at hand. Days were long (particularly during the last two weeks), but it all felt more than worth it at the end of the experience."

At the Birkdale clinic, the Miami students said they saw younger patients struggle to focus on their therapy.

Eric Lee, senior mechanical engineering major, demonstrates an initial prototype.

"The cycling machines available were difficult for the patients to use because the associated games were neither intuitive nor were they engaging after more than a few minutes of gameplay," the team wrote in its report.

They designed two fun games with multiple levels that allowed the children to maneuver characters in certain directions by using handgrips equipped with sensors.

One game operated in one dimension (left and right) and the other game operated in two dimensions (left, right, up, and down). The team said this allowed for further advancing of patient ability but also gave forward and backward pedaling different meaning to the player.

Their final prototype was built for about $200, a fraction of the cost of what some therapy cycles sell for — something that impressed Bondarenko.

"It was exciting that it is possible," she said.

The students said the final model was created to prove the design concept and usability, but future work is planned related to the aesthetics of the cycle, as well as the quality, length and features of the video games.

"Our project still would have a long way to go until real-world use," Lee said, "but when the therapist asked if she could keep our prototype, I'd say the whole team felt pretty satisfied."