Misinterpretation of early archaeology led to stories of aliens and witches

By Carole Johnson, university news and communications

Where do all these ideas and stories about aliens and witches come from? Archaeology can explain, says one Miami University anthropologist.

Jeb Card’s latest book, Spooky Archaeology: Myth and Science of the Past (University of New Mexico Press, 2018), traced the roots of many of today’s myths to the Victorian era and in the early twentieth century, before the field of archaeology became professionalized.

Ancient aliens and witchy rumors! How does folklore become fact over hundreds of years? One @miamiuniversity professor points to archaeology.

— MiamiOH News (@MiamiOHNews) October 30, 2018

In his latest book, Jeb Card (@ahtzib) debunks popular conspiracies and finds truth in fake facts.

Read more: https://t.co/ywapUiZ5WS pic.twitter.com/JLnCPCY97d

What he found was a series of events that led to misinterpretation and misrepresentation of archaeological finds. These created beliefs in the paranormal and established the roots of today’s conspiracy theories.

It’s about “real” versus “alternative” archaeology, said Card, an assistant teaching professor of anthropology. “Real archaeology provides the basis for human identity. Alternative archaeology provides the basis for conspiracy theories and overarching paranormal belief systems.”

Take for instance, the presence of “oddly” (to outsiders) shaped ancient skulls in South America. Victorian-era and later alternative-minded scientists would create narratives based on Theosophy.

“Led by H. P. Blavatsky, theosophists claimed secret knowledge received from ascended masters of lost root races and civilizations,” Card said. “They believe they came from lost worlds (think the lost city of Atlantis), located on sunken continents, and in some versions, contacted beings from beyond Earth.”

However, looking at the scientific facts, the “odd”-shaped skull can be explained.

“People of the Paracas culture of southern Peru two thousand years ago, like those in other cultures around the world, bound children’s heads for reasons of aesthetics, group identity and other motives,” Card said.

“This might seem strange, but then what would people from another culture make of binding our children’s teeth with plastic and metal and pushing them to reshape the jaw for aesthetic purposes? We call this ‘braces.’”

Although those early theories were thrown out by the mainstream scientific community, they provided fodder for later alternative ideas, some benign, some much more dangerous.

“Margaret Murray, an early archaeologist, reinterpreted the Early Modern (16th and 17th centuries) witch panic and trials as evidence of an ancient pagan cult,” Card said. “This idea would be instrumental in the creation of Wicca and other neopagan religions in the 20th century.”

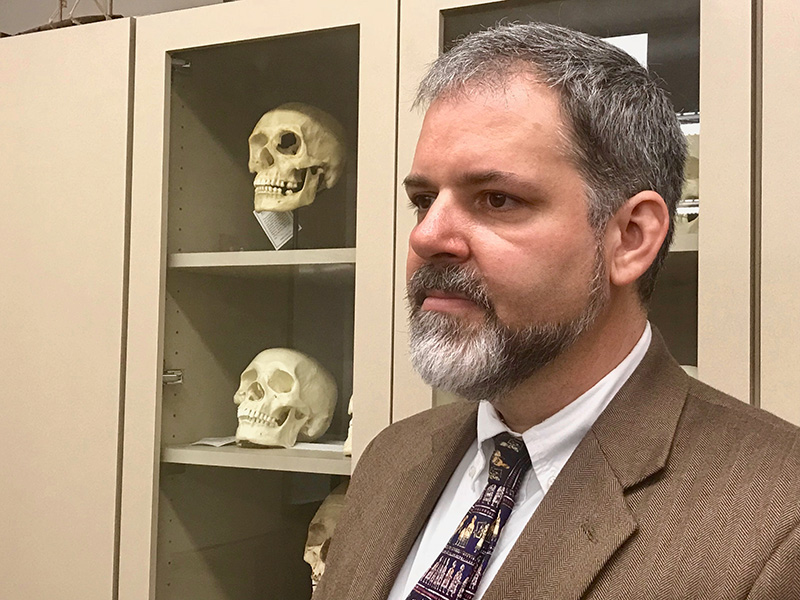

Jeb Card, assistant teaching professor of anthropology. Photo by Shavon Anderson

Fiction over fact

Blavatsky and Murray’s generally positive narratives combined together became the catalyst to what we know today as pulp fiction, but with a de-emphasis on the word ‘fiction’ and a decidedly darker cast.

“H. P. Lovecraft, considered a horror author in the 1920s, pioneered many of the techniques and tropes that today underpin large amounts of popular culture including movies, comics, video games, literature, and alternative "facts" and conspiracy theory,” Card said.

Although his works were fiction, a fact he stated over and over again, he did cite Murray’s essays, giving the stories an air of reality. These fictional stories then became the seeds of conspiracy theories about ancient extraterrestrials and secret societies that are today believed by large numbers of people.

Lovecraft’s popularity increased at the same time mainstream media published numerous stories about ancient archaeological discoveries, like the tomb of King Tutankhamun. During the period between the world wars, newspapers like The New York Times added to the popular belief that archaeology is dangerous and mysterious with stories of dead archaeologists and reports of overzealous searches for sunken cities.

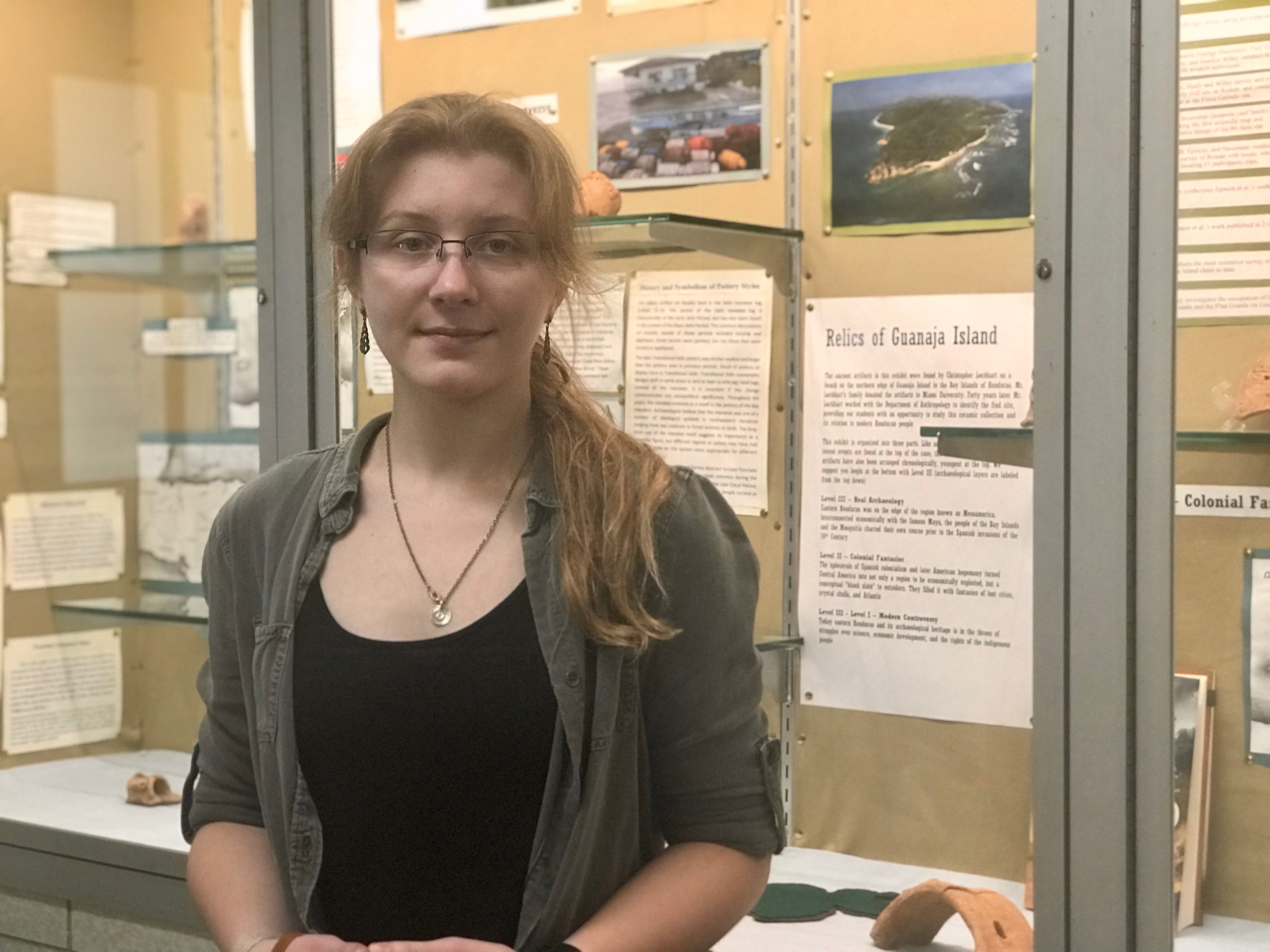

Miami junior Emily Ratavsky stands in front of a showcase that debunks popular myths and modern-day conspiracies. Photo by Shavon Anderson

Miami junior Emily Ratvasky shows these prominent themes in detailed drawings she created for Card’s book. Ratvasky began working with Card during her freshman year. Noting her artistic talent, he asked her to create artwork to illustrate his charts and graphs. “My charts were boring,” he said.Over the course of a semester, the anthropology major created an artistic story of Card’s research. She added imagery to highlight the influences of the time, including intricate facts, even down to the book titles of Lovecraft and other fictional authors works of the time.

These fictional characters were just that, fictional.

And, Card said, “Laughing at some of the colorful characters of today’s television and film may seem amusing to non-believers, but these ideas have played a huge role in mainstreaming attacks on scientific knowledge and methods and the advancement of conspiracy theory and political extremism.”