What tombstones can tell us

Roman Surnames

Aelii

Caecilii

Granii

Licinii

Lucretii

Sextilii

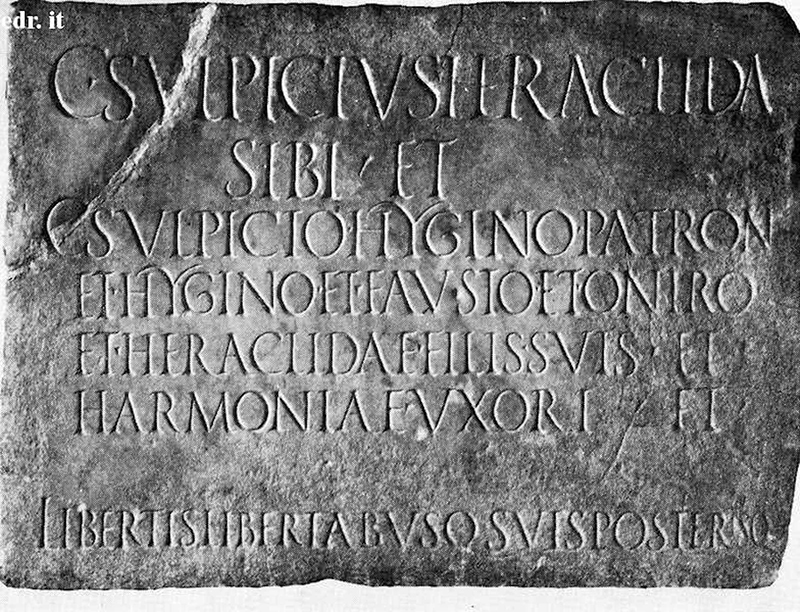

Sulpicii

Professor finds survivors from eruption of Mount Vesuvius

Ruins of the ancient city of Cumae hold hidden data. (All photos provided by Steven Tuck.)

By Carole Johnson, university news and communications

Try tracking your ancestors without the help of technology. Miami University professor Steven Tuck used 2,000-year-old records and found survival and prosperity in 79 AD.

Many of us are familiar with the catastrophic eruption of Mount Vesuvius that wiped out the ancient cities of Pompeii and Herculaneum. But did you know there were survivors? Scholars say a majority of them escaped.

Picture 20,000 people fleeing the eruption — some walking, running and others on wagons, many using pillows to cover their head. The historical letters of Pliny the Younger, a Roman who lived during the eruptions, describe the scene.

So, where did they go? Tuck found them.

They escaped to neighboring harbor towns and cities — Nola, Naples, Cumae

But how do you track people without readily available census data? Tuck began reading Roman surnames and inscriptions on tombs.

“Tomb inscriptions tell you not just that somebody lived and died, they give you their connection to the place,” said Tuck,

Steven Tuck, right, examines inscriptions, which led to

Eight categories of evidence + seven Roman surnames = survivors

Tuck developed a rigorous eight-step process and tracked seven family surnames that he believes relocated from Pompeii.

Evidence-based Categories

- Specific names of individuals found in inscriptions on tombs.

- Changes in the profile of a community based on family names.

- The appearance of new Tribus in the

refugee communities (members of a Roman voting tribe usually listed as part of one's name) that didn't previously appear in a community. - Explicit indications of origins (for instance, inscriptions of the word 'resident').

- Intermarriage between two or more refugee families.

- Material cultural that indicates Vesuvian lands, such as cults of deities prominent in Pompeii but new in the

refugee community. - New public infrastructure indicating larger populations such as the amphitheaters, roads, aqueducts.

- Human remains,

indicating mobility.

As his findings have been hitting the news, Tuck is surprised by the number of calls from people looking for their ancestors. He politely sends them his study, “Harbors of Refuge: Post-Vesuvian Population Shifts in Italian Harbor Communities,” but doesn’t go any further with them in their searches.

His study has been mentioned in numerous media outlets around the world. This fall,

From one of the largest homes in Pompeii, this preserved mosaic from Have House of the Faun was found under mounds of volcanic ash.

The idea for the study sprouted from a casual conversation Tuck had with his doctoral supervisor decades ago. Visiting the Bay of Naples at the site of the ancient city, he wondered out loud about all the infrastructure.

In essence, these survivors were refugees. Did those towns accept them or turn them away? What was the role of the government?

It appears that these survivors successfully relocated into their new communities. Tuck found financial records of one family,

“I can find no evidence of resistance to these people settling in,” he said.

Increased populations + Roman government = new infrastructures

Tuck attributes this lack of resistance to the fact that the Roman government stepped in and provided large financial support to these communities. For instance, to accommodate the increased populations in these cities, the imperial government built two new amphitheaters that mirrored its year-old, state-of-the-art Colosseum in the heart of Ancient Rome.

“This is huge,” Tuck said of the influx of new construction. “It’s as though Yankee Stadium is built and then a year later the government decides that’s the latest thing in baseball fields, we’re going to build a Yankee Stadium in Houston for all the Hurricane Katrina refugees. And suddenly this community has this immense, amazing new technological infrastructure.”

Tuck concluded that people made decisions on where to flee based on social and economic networks. The Roman government did not dictate where survivors settled and instead responded to the new needs of those cities.

“I set out to demonstrate the role of government with this study as well, and the answer is that the Roman government mattered to these survivors,” he said.

Next on his list is to use this process to explore the notion of survivors from Jewish and other non-Roman communities that lived at Pompeii and Herculaneum.

He also wants to use his Pompeii database to look for other survivors outside the area, such as Rome and other communities in Italy outside Campania.

“It’s tedious but intriguing,” he said of his process.

The Pozzuoli amphitheater is an example of new infrastructure built through funding from the Roman government.