A mission to give back is the result of some "much-needed" guidance

One student's journey leads her to the Peace Corps

By Shavon Anderson, university communications and marketingAll you can bring are two 50-pound suitcases. Addie Joson (Miami ’19) hasn’t started packing, but she has a loose list of necessities to take in January.

“Bug spray, peanut butter...” she laughed. “I’ve definitely got my priorities straight.”

It took months to get clearance, but when the official Peace Corps acceptance arrived, she wondered if she’d signed up too soon. The 27-month assignment in Ecuador limits family contact and discourages visits home – a considerable change for the first-generation American who leaves behind an inseparable Filipino family.

On an early Saturday morning, Addie and her mom, Charmaine, sit in the kitchen of their Dayton home. Laughter fills the living room where Addie’s siblings Victoria, 18, Olin, 16, and Lydia Reese, 5, flip through family photo albums while Lolly and Dodo (grandmother and grandfather) watch.

There’s a long pause as mother and daughter reflect on years past. In their silence, so much is said: love, pride and regret. Tears well in Charmaine’s eyes.

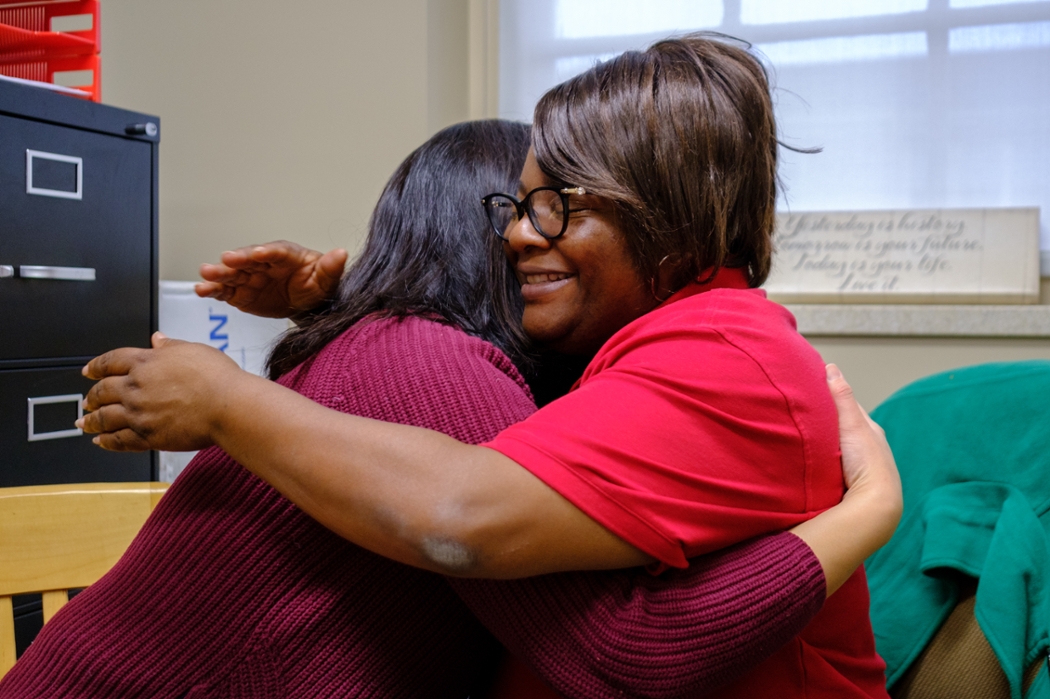

Addie and her mom Charmaine talk about Addie's journey to graduation (Photos by Scott Kissell).

“As a mom, you want to do more,” she said. “Addie had to grow up fast.”

Addie added, “It was just the situation we were in.”

Since she was a teenager, Addie’s acted as a second parent to her siblings, taking on immense responsibility and mostly raising herself. In some ways, the Peace Corps is an escape. In reality, it’s a lifelong dream. Either way, the timing is perfect.

Growing up, Addie’s grandparents shared stories about life in the Philippines before escaping martial law and immigrating to the United States. She knew she wanted to create equal opportunities for education and work to uplift similar communities, even if Lolly hoped for a more traditional path.

“She’s a little upset,” Addie said. “She left the Philippines for us to have a better life here, and now I’m going back to a country just like it.”

On this day, Lolly is quiet on the subject, bustling in the front hallway among stacked cardboard boxes. It’s part of a tradition, she said, to collect items throughout the year and ship them back to the Philippines for the holidays. Inside, there’s everything from clothes and toys to school supplies. She drops in an armful of coats and folds the flaps shut.

In Lolly’s eyes, behind the family’s laughter and in Charmaine’s voice is an unavoidable truth; soon, one of their strongest anchors will be 3,000 miles away.

Contending with culture

Growing up, Addie was immersed in the family’s deeply-proud Asian and Spanish culture. But it exposed her to early prejudice. She avoided speaking Tagalog and Spanish after being bullied during a short stay in a “small, close-minded town” – one of half a dozen Ohio communities she lived in through middle school.

“There were maybe 30 students in the graduating class,” she remembered. “Getting dropped off, I’d beg my parents not to speak to me.”

Though Addie grappled with identity and instability, she excelled in school, watching both parents finish college. But in high school, her parents divorced and Charmaine moved the family to Oakwood, a Dayton suburb. The split forced Addie into a parenting role as the oldest of three while Charmaine became the sole provider.

“I’d leave notes and money or a crockpot cooking. Addie would make sure the kids’ homework got done, their clothes were washed and dishes and chores were finished,” Charmaine said.

Addie and her siblings Olin (far left), Lydia Reese and Victoria (far right).

Addie found refuge in softball, managed the wrestling team and tutored after school. Frustrated, she understood the main principle of Asian culture –– family first.

When it came time to apply for colleges, Addie had national scholarship offers as a softball standout. It was her chance to leave.

“Then before graduation, my mom told me she was pregnant,” Addie said.

So, she enrolled in the physical therapy program at Sinclair Community College in 2014, prepared to step up again.

Creating stability

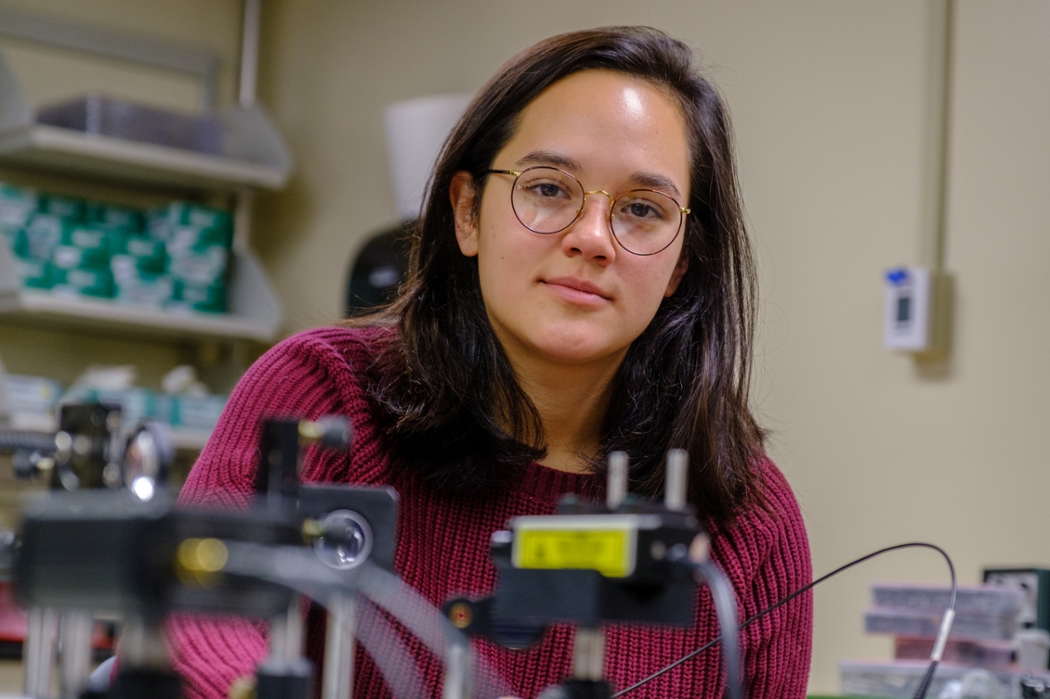

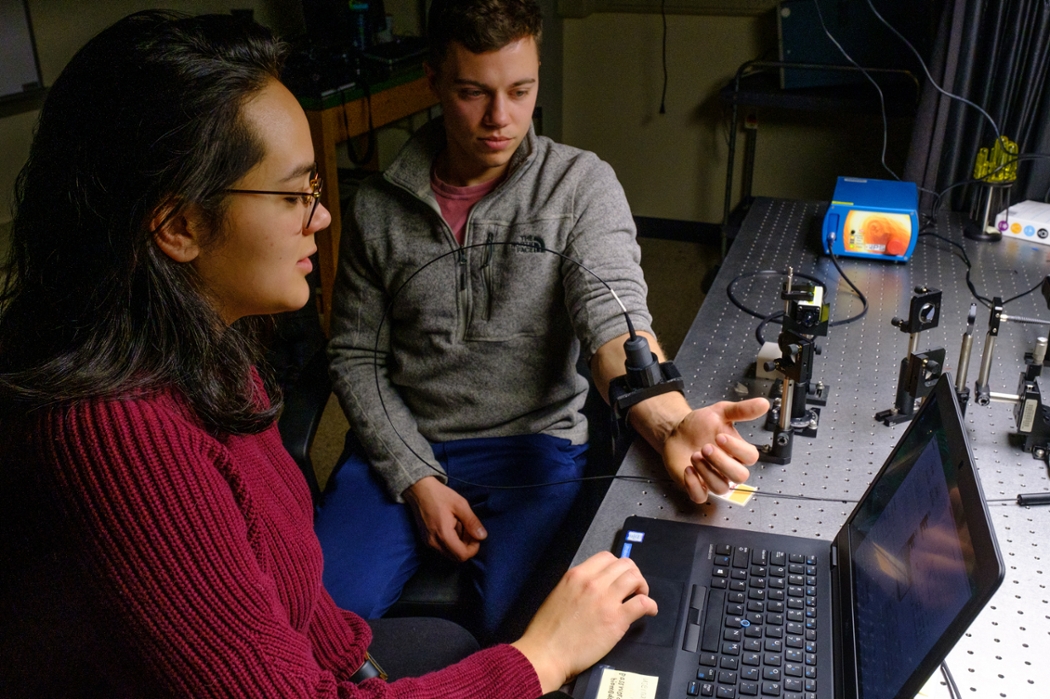

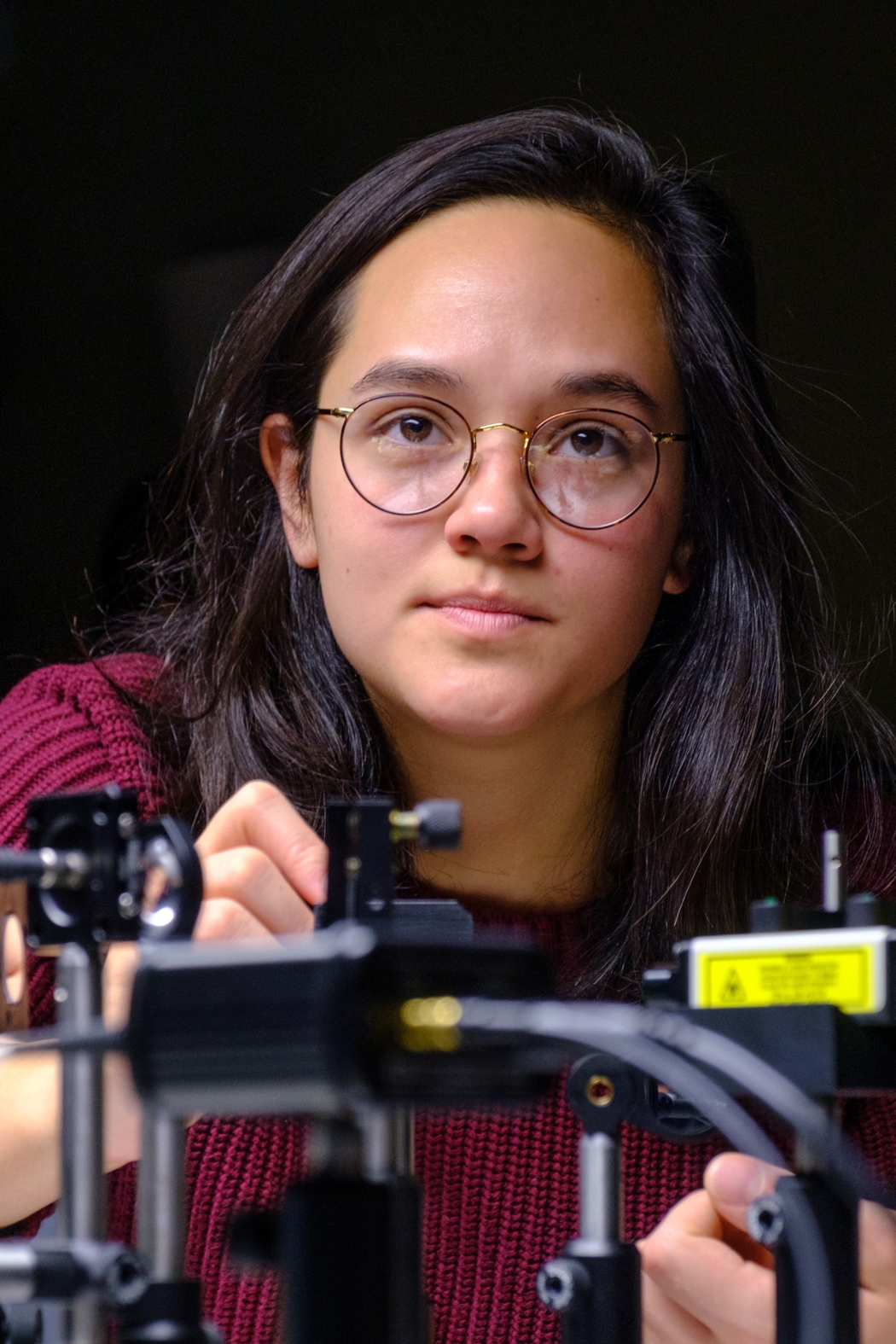

It’s Friday, Dec. 6, a week before Miami’s fall commencement. Addie arrives at the Optical Spectroscopy and Imaging Methods (OSIM) Lab in the basement of Kreger Hall, sits at a workstation and gestures for another student to join her before pulling out a monitor, slipping a strap up his forearm and wiring it into a laptop.

“A lot of people think research is a bunch of ‘Eureka!’ moments,” she said with a smile. “This is it.”

The room goes black, and she hovers over a monitor.

“I’m using a light source to detect changes to biological systems. Basically, looking at how blood flow is affected by things like nutrients or pressure,” she added.

Addie watches a monitor for research inside the Optical Spectroscopy and Imaging Methods lab.

Research brings Addie peace. It’s been a long road to this point now seven days until graduation.

After starting at Sinclair, she struggled to find herself. By year two, she had two associate degrees with no clear career, switched her major to engineering and continued supporting herself as family responsibilities increased.

“The stress made me sick, but I didn’t know how to say no,” Addie said. “One day we all clashed.”

She moved into an apartment and picked up a job where she had time to reflect. By her third year, Addie changed her major to chemistry and found much-needed guidance when a professor connected her with Kim Collins. At the time, Collins was Sinclair's LSAMP coordinator. LSAMP, the Louis Stokes Alliances for Minority Participation, is a federally funded program that works to increase and support underrepresented students in STEM-related fields.

Collins discovered how much Addie shouldered.

“At one point, she was bringing her little sister to daycare when she came to class,” Collins remembered.

Collins got Addie into research, helped her get a work stipend and registered her for conferences.

“They made resources available that I didn’t know were there,” Addie said. “I found a community that truly supports you. Kim is the most genuine, caring person.”

Addie and her Miami mentor, Kim Collins.

Part of Collins’ role was to help students transfer to four-year institutions. In 2018, she found a summer research program at Miami and urged Addie to apply. Addie met with the OSIM Lab team and later committed. Coincidentally, Collins accepted a position as Miami’s LSAMP coordinator that same summer and recruited Addie as a full-time student.

“I brought in 121 credits, and Miami took almost every single one,” Addie said.

She worked a research position in Oxford while completing her third associate degree in Dayton. By fall, she moved to Oxford and started as a biophysics major.

A rough transition

Addie’s first semester exposed glaring differences between Miami and community college. Before, most of her classmates were working adults, and the structure reflected that. Now a bachelor’s program, along with research, a job and family obligations, forced her to adjust mentally and financially. She felt isolated as a nontraditional student and went from having a full Pell Grant to applying for financial aid. Collins acted as a campus mom but said Addie never revealed the extent of her struggles.

“There were times where she didn’t have anywhere to live or anything to eat, and she didn’t have resources,” Collins said. “The food pantries weren’t open yet, and most of the resources go to first-years.”

Midway through the semester, Addie’s sister Victoria tore her ACL, adding another duty.

“I was going back and forth between Oxford and Dayton for physical therapy appointments, essentially soccer-moming,” she said.

Despite everything, Addie’s grit propelled her success in her first year. LSAMP provided steady support, she connected with a network of students with whom she traveled to conferences and participated in Alternative Spring Break, and she thrived in the lab under faculty lead Karthik Vishwanath, assistant professor of physics. Addie said the pair met after a research forum in 2017 where Vishwanath encouraged her current path.

“She remembers asking me if she should transfer to Miami to pursue engineering. Apparently, I'd responded with, ‘Yes! But why engineering? Come and become a physicist!’” Vishwanath said. “Sure enough, she did.”

He credits Addie with establishing new areas of research in her field and setting up systems that are now well established in the lab. She's been selected twice to present at the Annual Biomedical Research Conference for Minority Students and participated at the undergraduate research forum.

Meanwhile, Addie found time to give back. She worked in the LSAMP Early Arrival Program, which prepares incoming students for college-level work, and managed a nightly tutoring program for engineering students.

As the spring 2019 semester wrapped, Addie discovered she was eligible to graduate in December. Then, she lost her housing.

Planning for life abroad

Addie and Megan Cremeans (Miami ’20) like to joke about how they met.

“It was my first summer at Miami before I started classes,” Addie said. “Megan was mildly homeless."

The pair bonded through family similarities and values: Addie, a first-generation American and Megan, an Appalachian Ohio native. This past summer revealed the depth of their short friendship when Addie’s landlord declined to renew the lease for an early graduate.

Megan didn’t hesitate to offer a place to stay, echoing common themes seen across Miami’s community: the value of support, building connections and growing a network of lifelong relationships.

Addie and Megan Cremeans (Miami '20).

“In college, you meet people so fast but there’s also a willingness to jump into a friendship with someone,” Megan said. “You learn to trust other people as you learn to trust yourself.”

“Truly, there’s nothing like it,” Addie added. “The connections I made here are unbelievable.”

Addie calls her last summer at Miami “perfect,” rooming with friends and preparing for life abroad. Miami’s Student Success Center found her fall housing a week before classes started.

As the reality of life after Miami sets in, Addie exudes wisdom and appreciation.

“I eventually stopped trying to be so independent,” she said. “No one gets where they are without the help of others.”

Collins wrote Addie’s Peace Corps reference letter, detailing the inspirational student’s journey and mission to touch the lives of developing communities, similar to her family’s background.

“For someone who has gone through what she has, and to accomplish what she has, it’s rare,” Collins said. “She could be bitter or selfish, but she’s thoughtful, humble.”

Top row: Victoria, Addie, Olin. Bottom row: "Lolly," "Dodo," Lydia Reese and Charmaine.

In the Corps, Addie will teach English and expects to volunteer in a science-related cohort while immersing herself in food and culture. Charmaine is prepared for her oldest to step out on her own, and Addie’s siblings are old enough to need her a little less, though that reality doesn’t make the time and distance less painful.

When Addie’s commitment ends, she’ll apply to graduate school. Through LSAMP, she’s eligible to go for free. But for now, she’s not stressed about the future.

“I’ve learned not to have expectations,” she said. “Every plan I’ve had has pushed me a different way. Somehow, I’m always where I need to be.”