A golden opportunity: Miami geologist studies world's largest single crystals of gold

"The structure or atomic arrangement of gold crystals of this size has never been studied before and we have a unique opportunity to do so," – John Rakovan

The world's largest single crystals of gold were hosted at Miami's Shideler Hall during winter term. Mineralogist John Rakovan – the first scientist to examine the crystals for authenticity – has been studying the crystals for several years with colleagues Heinz Nakotte and Sven Vogel of the Los Alamos National Laboratory Neutron Science Center.

Forensic geologyThe purpose of the study is twofold. "The first is a bit of forensic science. Because of the spectacular size and perfection of some of these samples, their authenticity as real, naturally formed single crystals has been called into question. There is no doubt that they are gold, said Rakovan, who is a professor of geology and environmental earth science at Miami and an expert in crystal structure.

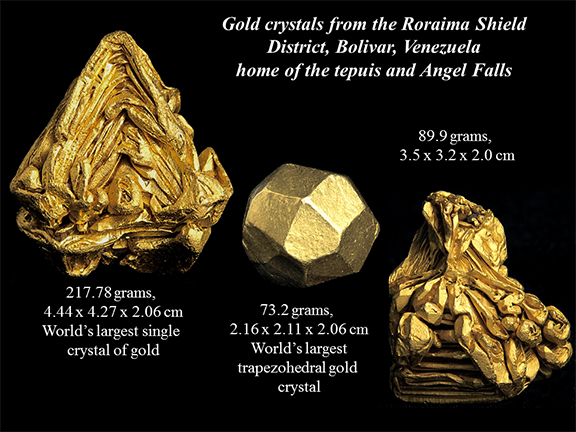

There have been gold nuggets as big as several feet in diameter, but single crystals are usually quite small. It is rare for a single crystal of gold to be formed in nature the size of these world's largest crystals, according to Rakovan. The largest single crystal of gold is less than two inches wide (at left in photo).

"The question is whether Mother Nature is responsible for their beautifully faceted shapes. One alternative is that they were cast and made to appear as large single crystals," Rakovan said.

"If they are real, and we now know that most of them are (although we have not finished our work so some are still in question) then there is great scientific interest in the nature of their crystal structures and how they may have formed. Answering these questions is my main goal."

Rakovan traveled to New Mexico with the gold crystals earlier this month. The crystals are stored at Los Alamos National Laboratory under high security.

After further experiments the gold crystals will be returned to the owner.

Where did the gold crystals come from?

The samples were all collected, over a 30-year period, in the jungles of the Roraima Shield District and the Gran Sabana, Venezuela, home of the tepuis (table-top mountain or mesa) and Angel Falls, Rakovan said. Gold is found in placer deposits - the sediments of river bottoms between the mesas. The gold is weathered from its original host rock, transported by streams or rivers and deposited with sediment.

The samples are owned by an individual from North Carolina. "He lived in Venezuela with his business partner for 30 years, during which time they bought and sold diamonds and gold from the area. The crystals that I am studying are the best ones that they acquired and have kept in their personal collection," Rakovan said.

In 2006 these large specimens went up for auction, but the authenticity of one was questioned (the "golf ball," world's largest trapezohedral crystal of gold, middle in photo above) and was subsequently pulled off the auction.

Because of his expertise in gold crystallography, Rakovan was given the rare opportunity to study these samples.

Unlocking the puzzle: authentic single gold crystal or polycrystalline?

The smaller, mounted gold crystal at right was the original specimen studied by Rakaovan that unlocked the key to the puzzle of single gold crystal authenticity.

Rakovan analyzed the first specimen using X-ray diffraction. Results from analysis of many different faces of the crystal indicated polycrystallinity – but one face showed a single-crystal pattern.

The results puzzled Rakovan, who wondered whether the gold was actually a single crystal that had been deformed on the surface (such as in tumbling through a stream bed during stream transport).

Rakovan needed to "see" the inner structure of the crystal to determine whether it was a single crystal — with an atomic structure that is periodic — or polycrystalline — with an atomic structure with interrupted periodicity.

"All but a singe face on one crystal exhibited polycrystallinity; therefore neutron diffraction data were the key to answering the question of single-crystal authenticity," Rakovan said.

Neutron diffractometry – a look inside

Rakovan and his colleagues at the Los Alamos National Laboratory Neutron Science Center used neutron diffractometry to solve the puzzle: Are the large crystals actually single crystals of gold that have been mechanically deformed (tumbled), or are they polycrystalline?

"Using neutrons that are created by smashing apart tungsten or mercury atoms we are able to 'see' into the center of these large and very dense crystals to determine the nature of their crystallinity and how they may have formed," Rakovan said.

"Previous studies using X-rays have been insufficient because they are so quickly absorbed by heavy elements like gold."

John Rakovan with gold crystals (the largest are now housed at Los Alamos National Laboratory).

While X-rays will only penetrate the surface of these crystals, to depths no greater than a few hundredths of one millimeter, neutrons can travel one to two centimeters into gold.

Rakovan and his colleagues determined that the specimens in the photos at right and above are single gold crystals; further experiments will be conducted on the "golf ball" specimen.

"By determining the nature of their crystallinity we will have a better understanding of how they formed and the processes that occur during weathering and transport to their final destination in a placer," Rakovan said. "One possible use for such information is in prospecting for the original rocks in which the gold was formed."

Rakovan, who has a mineral named after him - Rakovanite - is also the executive editor of Rocks and Minerals.

His original study of the gold crystals, "Characterization of Gold Crystallinity by Diffraction Methods," included undergraduate Nina Gasbarro (Miami '12) who conducted some of the X-ray diffraction analysis. Gasbarro is now a doctoral student in chemical engineering at the University of Michigan.

Rakovan is currently attending the 60th Annual Tucson Gem and Mineral Show, "60 Years of Diamonds, Gems, Silver and Gold" (Feb. 13-16) from which he reports there is much discussion about the results of the gold crystal research.

Written by Susan Meikle, university news and communications, meiklesb@MiamiOH.edu.