Opt-out movement in Ohio small but significant, say Miami researchers

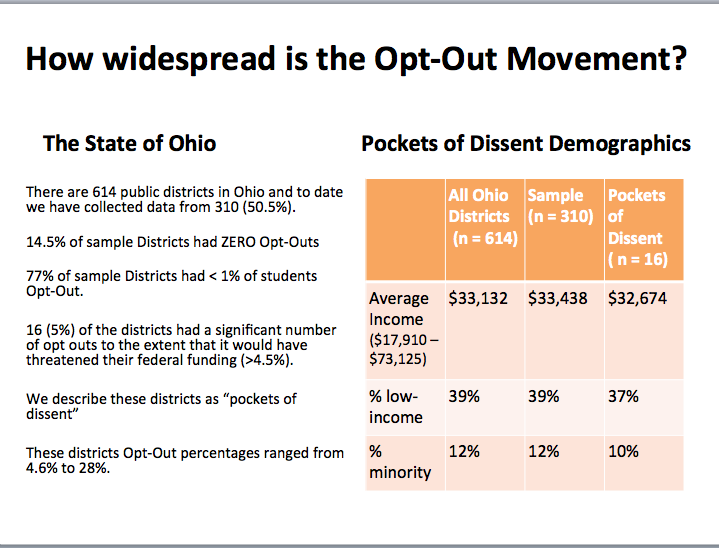

Preliminary data from Evans/Saultz research. (Graphic courtesy of Michael Evans.)

by Carole Johnson, university news and communications

Michael Evans and Andrew Saultz wanted to learn more about the national movement to opt out of standardized testing. They started with Ohio, discovering not widespread, but distinct pockets of dissent.

The scope of Ohio’s opt-out movement surprised the two researchers, both professors in Miami University’s College of Education, Health and Society. They found in preliminary data that the media portrait painted of the affluent suburbia parents leading the charge is not the case at all.

“Pockets of dissent are materializing in a wide range of districts — not only the affluent suburban or urban school districts as many believe,” Evans said.

Halfway into their research they discovered that 5 percent of the districts had a significant number of opt-outs. These districts represent typical Ohio communities. (See chart right.)

Evans and Saultz are now turning their attention to the rationale that informs a parent’s decision to opt out of having their children take the tests.

In Ohio there are two organizations that appear to be very influential: United Opt Out – Ohio, a progressive education group; and Ohioans Against the Common Core.

United Opt Out members believe testing is taking away time and resources from the arts and other forms of curriculum. They also are concerned about corporate influence on public education. Ohioans Against the Common Core dissenters hold the belief that the federal government wields too much control over local school districts.

”It’s a combination of strange bedfellows in terms of who is supporting the opt-out strategy,” Evans said.

Evans is an assistant professor of teacher education, educational leadership, and family studies & social work.

Evans part of Education Week webinar June 17

In a June 10 opinion article published in Education Week, Evans and Saultz argue education policymakers must listen to parents’ concerns. Rather than push them to the margins, they need to engage them.

“These pockets of dissent are significant and may signal the beginning of a broader change movement in public education,” the two write in the editorial.

Evans will be among presenters in a live webinar for Education Week June 17. The webinar is free, but registration is required.

Research continues

Their curiosity piqued, Evans and Saultz work to finish phase one and head into phase two of their research.

Q: What other surprises have you found in your research?

A: (Saultz) We were surprised that the opt-out movement is not spread evenly across the state. Some districts show a large number of opt-outs, while others show none at all. In addition, at this time the state is not tracking these numbers. We had to call each of the districts and ask them their numbers.

Q: Are there too many tests?

A: (Evans) While that question is not a part of our research, I can say that high-stakes testing has transformed the way many schools interact with students. I have visited several schools where administrators have data rooms with white sheets of butcher paper covering the walls listing all the students in the school. The lists are color-coded, highlighting the students who should pass and those who will struggle on the tests. Their goal is to target resources for those students who are on the bubble. The risk here is that the focus is being placed on a school’s overall score and not on the needs of individual students.

Saultz is an assistant professor in educational leadership.

A: (Saultz) No one knows what the breaking point is for too much testing. The No Child Left Behind Act focused on reading and math; critics wanted testing of science and social studies added. These additions make sense to address the concern about a narrowed curriculum but may have created new problems. Now there is Common Core and PARCC (Partnership for Assessment of Readiness for College and Careers), which have substantially increased the amount of time students spend taking tests. I think we are approaching that limit if we haven’t reached it already.

Q: Is this grassroots effort beginning to make an impact?

A: (Evans) In Ohio, the potential is there. In March, Ohio policymakers passed legislation that will protect opt-out students from some potential consequences of not taking the tests. We will have to wait and see if bigger issues like the adoption of the Common Core and the use of the PARCC assessments will be impacted.

Q: What are your next steps in the research?

A (Saultz) Once we finish the initial data collection, we want to visit school districts with high numbers of families opting out to learn what people are saying and how the school districts are or are not engaging families in the process.