A cultural reawakening: Myaamia ribbonwork connects tribe students with their ancestors

Third of a three-part series about Miami University's ongoing partnership with the Miami Tribe of Oklahoma

By Margo Kissell, university news and communications

Myaamia tribe members Ian Young, Jackie Mooney and Evan Theobald wearing their 2016 commencement sashes.

Ian Young graduated from Miami University last spring with majors in physics and philosophy, but his college experience also deepened his understanding and appreciation of his Myaamia Tribe heritage.

The Illinois native said it shaped his identity: He is learning to speak the language, participated in traditional storytelling at the annual winter gatherings in Miami, Oklahoma, and worked as a counselor in the summer youth program there.

He also stitched by hand two pieces of Myaamia ribbonwork featuring the tribe's distinctive geometric patterns.

The artwork is part of an ongoing cultural revitalization led by the Myaamia Center, a collaboration between the university and Miami Tribe of Oklahoma. (Myaamia is “Miami” in the Miami language.)

Young explained that when tribe members tell stories at gatherings, they view it as picking up a thread, carrying it for awhile and setting it back down until it’s picked up again at the next telling.

“When participating in the games, in the art forms, in the language, what all of that is, is me picking up that thread that was set down by my family so long ago and continuing to carry it forward,” he said.

Reawakening a dormant art form

The art form of peepankišaapiikahkia eehkwaatamenki (Myaamia ribbonwork) grew out of the 1700s trade era when the Myaamia people acquired silk ribbons from European traders. They used the ribbons in such bold colors as red, black, white, yellow and blue to decorate clothing the men and women wore for special occasions, as well as moccasins, bags and other belongings.

The culture and language declined in the 20th century because of forced relocation and schools requiring Native Americans to learn European culture and language and abandon their own. By the early 1960s, the last tribe member to speak Myaamia conversationally had died. “We began to lose our sense of continuity, and much of our communal understanding went to sleep,” wrote George Ironstrack (Miami ’06) and Scott Shoemaker in an 85-page handbook on ribbonwork the Myaamia Center published this year.

The culture and language declined in the 20th century because of forced relocation and schools requiring Native Americans to learn European culture and language and abandon their own. By the early 1960s, the last tribe member to speak Myaamia conversationally had died. “We began to lose our sense of continuity, and much of our communal understanding went to sleep,” wrote George Ironstrack (Miami ’06) and Scott Shoemaker in an 85-page handbook on ribbonwork the Myaamia Center published this year.

The publication, co-authored by Andrew Strack, Karen Baldwin and Alysia Fischer, is the result of a $30,000, two-year grant from the National Endowment for the Arts that the Myaamia Center received in 2014 to teach the skills and share the knowledge so tribe members could revitalize the lost art.

The grant also funded a series of workshops in 2015 and 2016 held on campus, in Miami, Oklahoma, and in Fort Wayne, Indiana, as well as three, online demonstration videos featuring Karen Baldwin, special projects/researcher for the Miami Tribe of Oklahoma, who has led some workshops. Shoemaker, a member of the Miami Nation of Indians of the State of Indiana, Inc., led others. But first, they had to learn how to do the ribbonwork themselves.

Interest in ribbonwork growing

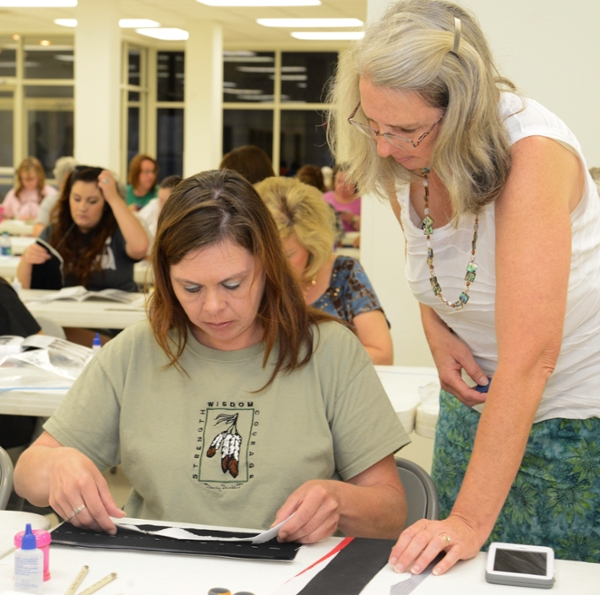

Karen Baldwin teaches a 2015 ribbonwork workshop in Miami, Oklahoma.

Karen Baldwin, a seamstress who began sewing at age 10, learned it from two Delaware Tribe women who were doing ribbonwork. She and Daryl Baldwin, her husband and director of the Myaamia Center, had seen examples of their stunning artwork in the mid-1990s during a workshop in Indiana.

“We thought ‘That used to be an art form of ours,’ and so we began to relearn it. Much like our language, we had to relearn it,” said Daryl Baldwin, who last week was named a 2016 MacArthur Fellow for his cultural revitalization efforts.

A major boost came in 2003 when the Miami Tribe of Oklahoma received a Native American Graves Protection and Repatriation Act Documentation Grant from the National Park Service. It allowed tribe members to travel to institutions to view Myaamia ribbonwork and other objects in their collections. Many had never been displayed.

“That was the first time a lot of us had seen historical pieces of Myaamia ribbonwork,” Daryl Baldwin recalled. The photographs they took were archived and became an integral part in developing the Myaamia Ribbonwork Project.

Nearly 175 workshop participants have learned the Myaamia ribbonwork process that involves layering, cutting, folding and sewing ribbons. Many of them have returned seeking to create second and third patterns. Karen Baldwin said she is honored to introduce others to the art form.

Since 2010, ribbonwork-adorned commencement sashes have been made for Miami tribe students who have graduated from the university. Karen Baldwin, who now makes all of those sashes, recently made a ribbonwork sash for Chief Doug Lankford of the Miami Tribe of Oklahoma to wear at the Oct. 10 inauguration of Miami President Gregory Crawford. The president will wear a medallion hanging on a newly hand-sewn ribbon adorned with red and white ribbonwork, also made by Baldwin.

The left side of Lankford’s sash lays over the heart and displays the Miami Tribe seal along with the words “niila myaamia,” which means "I am Miami." The right side displays the Miami University seal and “kiiloona myaamiaki,” which means "We are Miami."

Seeing the impact of reviving a culture

It’s lunchtime, and in the silence of his office in Roudebush Hall, Jim Oris sits at a small table creating Myaamia ribbonwork.

The associate provost of research and scholarship and dean of the Graduate School, who is Daryl Baldwin’s supervisor, is hard at work on his third piece.

Jim Oris sews ribbonwork in his office (photos by Scott Kissell).

Each has been more complicated than the last, as he draws on the basic sewing skills his mother taught her six sons when they were in high school.

“The smaller the diamonds get, the more difficult it is,” said Oris, who hopes to finish it by winter.

“For me, the ribbonwork is very powerful because it’s a visual display of the culture being revitalized,” Oris said. By the late 1980s, Myaamia language reconstruction began, with the tribe launching an organized effort in 1995. Oris has seen firsthand the impact of the ongoing cultural revitalization during his visits to Miami, Oklahoma, in recent years.

“You show up at a community gathering and there are small children talking in Myaamia to their parents,” he said. “The college kids sit down and they’re playing games and they’re communicating just in Myaamia. They’re joking and teasing and laughing in Myaamia, so they’re living it.”

Daryl Baldwin believes the young people will take the language and art forms and create something new. “It’s going to be something that reflects their evolving identities, and we encourage that,” he said.

Young, who has put the traditional ribbonwork pattern on his cellphone cover, said discovering his heritage at Miami changed his life. He is interning this year at the headquarters of the Miami Tribe of Oklahoma and hopes to go to law school so he can one day practice law to represent the Myaamia people.

“It gave me a purpose, a path and goals and a dream that I only could have gotten where I was,” he said. Today, he is among 60 Myaamia undergraduate students and six graduate students who have earned degrees from Miami University.

A record number of Miami Tribe students on campus

Ian Young (Miami '16) creates ribbonwork at a workshop. He is now an intern for the Miami Tribe of Oklahoma.

Oklahoma native Addison Patrick, a first-year student majoring in sport management at the Oxford campus, came up through the Myaamia Eewansaapita (summer youth experience) and worked as a counselor.

This fall, he is one of 35 Myaamia Tribe students on campus — an all-time high, said Bobbe Burke, coordinator of Miami Tribe relations.

Thirty-two of them are undergraduate students (including 10 freshmen) and three are graduate students. The record number comes 25 years after the first three Myaamia tribe students started at Miami. Like the other students, Patrick qualified for a Heritage Award, providing a tuition waiver because of his Myaamia ancestry.

Patrick learned how to create ribbonwork last year at a workshop he attended with his grandmother, mother and younger brother. “I think it’s neat how we’re kind of doing the same things our ancestors did,” he said.

It strikes close to his heart knowing that he is helping to keep the Myaamia culture alive.

He recalled how his great-grandmother, Mildred Walker, who died in 2012 at 98, knew the Myaamia language best, but would never speak it.

“It was the dark part of our culture, and it was kind of taboo to speak like that. That’s unfortunately how it all got lost,” Patrick said. “But now, times have changed and it’s celebrated, learning all of this.”

Read parts one and two of this series here:

Knowing their tribal identity helps Native American students succeed