Who’s watching you? New report details how digital advertising is being used as a political weapon

by Shavon Anderson, university news and communications

Matthew Crain, assistant professor of media and culture.

Your behaviors and emotions are being influenced right now, whether you realize it or not.

An invisible digital infrastructure is monitoring consumer profiles, targeting audiences and leveraging your data to mobilize political campaigns. That infrastructure is being used as a weapon, argues Matthew Crain, assistant professor of media and culture at Miami University.

“Most people don’t understand how these things work,” he said.

Crain co-authored a newly released report, “Weaponizing the Digital Influence Machine: The Political Perils of Online Ad Tech,” describing what the authors coined as the Digital Influence Machine and its ability to use targeted advertising in order to reach people at their most vulnerable.

The technique can be used in three distinct ways:

- Mobilize supporters through identity threats.

- Divide an opponent’s coalition.

- Leverage influence techniques informed by behavioral science.

Until recently, things went relatively unnoticed.

“The reason why we call this an ‘infrastructure’ or ‘machine’ is because you don’t notice it, until it breaks,” Crain said.

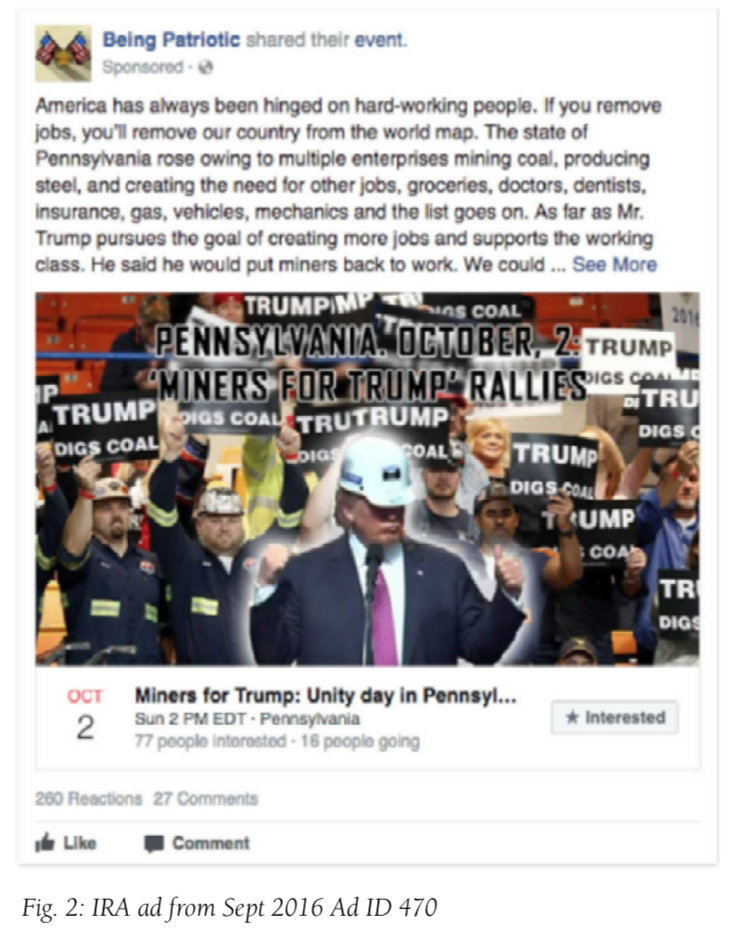

In September 2017, Facebook revealed that a six-figure ad spending campaign and around 3,000 ads were linked to Russian groups trying to influence the U.S. election. A federal investigation identified the Russian network, Internet Research Agency. It spent millions of dollars to spread disinformation and increase tension.

“Conversations about data breaches and privacy are becoming visible because of all the focus on foreign groups,” Crain said.

If you think you aren’t affected, think again.

Us vs. Them

Have you ever been online and come across an ad for something you’d just searched or a store you were just at? You’re being tracked.

“Tracking has been rationalized and sold to us as relevance,” Crain said. “Companies say, ‘We collect your data because we can serve ads that are in your interest.’”

In reality, a lot of that info is being used to peg your interests and hobbies, which can then be used by groups like the Internet Research Agency to fuel your emotions and behaviors. Crain’s report notes that while targeted advertising rarely changes someone’s deeply-held beliefs, it works to amplify their existing beliefs and increase resentment or anxiety. Those heightened emotions stir distrust and division and can persuade political behavior.

To get an idea of how manipulative targeted advertising can be, here’s an example from the report, showing a campaign aimed at African Americans.

A Facebook account initially promoted positive affirmations through posts about Black art and culture but shifted to posting messages that encouraged its users to not vote in the 2016 election. A similar campaign run by the Russian agency targeted Pennsylvanians who identified as conservative-leaning coal miners. It used intense rhetoric to connect with users, making them feel like their livelihood, self-esteem and contributions to America were under attack.

The fix

The report concludes with suggestions for reform and regulations.

“Policy is at both ends of this,” Crain said.

There are signs of slow progress in Washington. According to the report, 30 U.S. senators are co-sponsoring the Honest Ads Act as of July 2018, but partisan gridlock points to little hope of major changes in the near future. While some states like California worked to pass individual regulations, Crain says the Trump administration has largely been moving in the opposite direction.

“The 2018 election is already past. We’re talking about the 2020 election right now,” Crain said. “The decisions we make now, based on the scandals, are really going to impact future campaigns.”

It’s not just federal elections that are targets. Crain emphasizes that targeted advertising spans nationally and can affect any issue or campaign, down to municipal voters and even a school board decision.

You can read Crain’s full report online.