Emma Gould Blocker Fund

Your support of the Blocker Fund will directly benefit McGuffey House and Museum. An annual gift or provision in your estate plan will help ensure the Museum can sustain operations for many years to come.

As a National Historic Landmark, we aim to collect, preserve, interpret, and exhibit materials relating to the life of William Holmes McGuffey, the McGuffey Eclectic Reader series, the history of Miami University, and 19th-century domestic life and architecture of southwest Ohio.

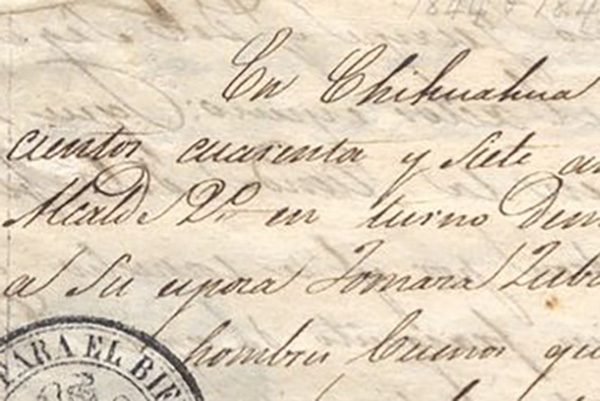

William Holmes McGuffey (1800-1873) was a Miami University faculty member in 1836 when he compiled the first edition of the McGuffey Eclectic Reader in this house. His Reader taught lessons in reading, spelling, and civic education by using memorable stories of honesty, hard work, thrift, personal respect, and moral and ethical standards alongside illustrative selections from literary works.

Learn MoreThe six-edition series increased in difficulty and was developed with the help of his brother Alexander Hamilton McGuffey. After the Civil War, the Readers were the basic schoolbooks in thirty-seven states and by 1920 sold an estimated 122 million copies, reshaping American public school curriculum and becoming one of the nation's most influential publications.

McGuffey lived at this site in a small frame house in 1828, and in 1833 built this brick home in the Federal vernacular style common to the area. The west wing was added about 1860 in the first of a series of renovations typical of nineteenth-century domestic architecture in the Miami Valley. From the 1850s to 1958 several Oxford families owned the property. At the Miami University Sesquicentennial in 1958, the University purchased the house from the Wallace P. Roudebush family, and it was endowed by Emma Gould Blocker to serve as a museum of University history in honor of McGuffey's legacy. The museum opened to the public in 1960 and the house was designated a National Historic Landmark in 1966. It exhibits such unique artifacts as the octagonal table upon which the McGuffey Eclectic Reader was designed and the lectern McGuffey used as professor of Ancient Languages and Literature and University Librarian.

"Luxury in the William Holmes McGuffey House & Museum" explores how McGuffey’s home reflects the aspirations of its time, blending architectural elegance, carefully chosen everyday objects, and ornamental items that serve as both status symbols and expressions of taste.

Our Museum Administrator and Curator, Jennifer Lorenzetti, can be emailed at any time to assist you with your research needs.

Researchers are welcome to book our research room during our normal hours of operation.

The House and Museum provides an educational experience for researchers and higher education students. In order to provide public programs and free access to all, the museum increasingly relies on donated funds for support. These funds help support a museum administrator, student employees, as well as the professional care of the collections the museum is entrusted to steward.

Your support of the Blocker Fund will directly benefit McGuffey House and Museum. An annual gift or provision in your estate plan will help ensure the Museum can sustain operations for many years to come.

The use of donated funds to the Sue and Ed Jones Fund may include, but is not limited to, marketing, educational programming, conservation of collections, and student wages

Looking for a souvenir from the museum? We have items from totes to mugs to ornaments. All items will be shipped directly to you.

Miami University and the City of Oxford offer several museums, libraries, and archives for students and community members alike to enjoy.

In addition to an energetic schedule of historic and contemporary exhibitions from around the world, the Richard and Carole Cocks Art Museum houses a growing permanent collection of approximately 17,000 artworks.

The Miami University Hamilton Conservatory maintains a scientifically-verified collection of plants to enhance the knowledge and appreciation of plants through public education and interpretive programs.

Located in Shideler Hall, The Karl E. Limper Geology Museum displays fossils of Southwestern Ohio as well as minerals, rocks, fossils, and meteorites from all over the world.

Considered visual laboratories, the programs of Hiestand Galleries exhibit artworks that highlight timely, enlightening, and challenging exhibitions that consider the ever-changing world of contemporary visual expression.

Located in Upham Hall, the Robert A. Hefner Museum of Natural History explores animal natural history, animal biodiversity, conservation and ecology.

The former home of the presidents of Western College previously housed the offices of the Western College Alumnae Association, Inc. Currently closed to the public.

King Library houses The Walter Havighurst Special Collections and University Archives, containing over 95,000 historical, literary, and cultural items. The archives chronicle the university's history, administrative business, and teaching activities. Materials include manuscripts, publications, maps, photographs, memorabilia, plans, electronic records, and official records.

The Willard Sherman Turrell Herbarium houses approximately 650,000 dried plants from around the world, including vascular plants, bryophytes, fungi, lichens, algae and fossil plants.

We aim to collect, preserve, interpret, and exhibit materials relating to the life of William Holmes McGuffey, the McGuffey Eclectic Reader series, the history of Miami University, and 19th-century domestic life and architecture of southwest Ohio.

Thursday - Saturday

1:00pm - 5:00pm

McGuffey House and Museum observes Miami University closings and other special events.