Yoshi Tomoyasu's evo-devo lab: Behind the scenes

By Susan Meikle, university news and communications

Tribolium castaneum, the red flour beetle.

In the last 200 years, scientists have been studying the origin of insect wings using various approaches, such as paleontology, taxonomy and morphology.

Yoshi Tomoyasu, associate professor of biology at Miami University, uses a relatively new approach, evolutionary developmental biology (often called ‘evo-devo’) to tackle the centuries-old debate about the origin of insect wings.

Recent research published by Tomoyasu and his students offers evidence of the dual-origin of the evolution of insect wings — one of the three competing explanations for how insect wings developed.

Read more about their research in the Miami news story "Tomoyasu's research helps solve the centuries-old mystery of the origin of insect wings."

Research such as this is powered in part by graduate and undergraduate students. Here are six highlights from Tomoyasu’s lab:

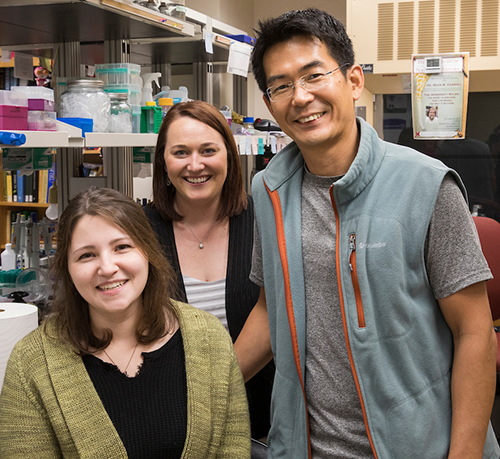

Left to right: Maddy Moe, senior; Courtney Clark-Hatchel, who received her doctorate in August; Tomoyasu (photo by Jeff Sabo).

1. "Yoshi,” not “Dr. Tomoyasu,” in the lab

He asks that students call him “Yoshi” and not “Dr. Tomoyasu” in the lab.

“The idea is that I want to be just another fellow scientist to them while in the lab,” Tomoyasu (or, Yoshi) said. He feels fortunate to have many talented students in his lab group.

2. Senior bioengineering major Maddy (Madison) Moe, Miami-Hughes intern

Moe, who is in her second year working in Tomoyasu’s lab, is one of 15 students who were awarded a Miami-Hughes internship for research in summer 2018. The internship provides a $3,000 stipend, $750 research expense and 12 hours of tuition credit waived for 10 weeks of mentored research in the biological sciences.

She has worked closely with Courtney Clark-Hatchel (Miami ’12, Ph.D. ’18) for about two years on the Tribolium beetle wing origin project.

Tomoyasu's lab has been a “great motivator,” Moe said. After receiving the Miami-Hughes internship and having her work published in a scientific journal this summer, she said, “Two years ago I never would have thought that these things would be possible for me, and I've only just begun to join the field.”

- She is a co-author with Clark-Hatchel and Tomoyasu on a study published in the July issue of Athropod Structure and Development.

- Their study showed that in Tribolium, two distinct tissues can independently transform into wings, offering evidence for the dual-origin evolution of insect wings.

Busy scoring mutant beetle larvae (front to back): Moe, Clark-Hatchel, former undergrad researcher Monica Hernandez and Shuxia Yi, research associate.

Moe feels "very strongly" that beginning work in undergraduate research has been a critical turning point during her time at Miami. “I've enjoyed my time in the lab immensely.”

3. Courtney Clark-Hatchel: From undergraduate to doctorate

Clark-Hatchel, who received her doctorate in August, has been a mentor to Moe and other undergraduates in Tomoyasu's lab. She began her research career with him, joining his lab as a first-year student at Miami in 2009. Her undergraduate research with him was supported by an Undergraduate Research Award and an Undergraduate Summer Scholar award, through the office of research for undergraduates.

After earning her bachelor's degree in 2012 she stayed at Miami for her doctoral degree. For her dissertation project with Tomoyasu, she was one of 2,000 graduate students nationwide to receive a prestigious fellowship from the National Science Foundation’s Graduate Research Fellowship Program in 2014. The fellowship provided a $32,000 annual stipend and $12,00 cost of education allowance for three years.

She began a postdoctoral research position at the University of North Carolina, Chapel Hill, this month.

4. Innovative lab course developed from an idea Tomoyasu had when he was an undergrad

BIO 464, a molecular biology lab course, is based on an idea Tomoyasu had when he was an undergraduate, and has "always wanted to try," he said.

In this course, students can discover the biological consequences in Tribolium beetles when a gene of interest is “turned off” using the RNA interference method. For instance, students might turn off genes that are thought to influence a certain behavior, organ type, shape or wings.

At the end of each semester students disseminate their results publicly on a website, BeetleWiki, for use by researchers and other students. The BeetleWiki database was created by Tomoyasu's current doctoral student Kevin Deem (Miami '14), who learned computer programming through his minor in bioinformatics at Miami. Deem will help teach BIO 464 next spring.

Tomoyasu and his graduate students published the experimental method in video form in the scientific journal, Journal of Visualized Experiments (JoVE), for use by students in his class — or in any class worldwide. View it at: Larval RNA Interference in the Red Flour Beetle.

The course has proven to be popular with students, Tomoyasu said, and is one reason why Moe was inspired to pursue undergraduate research with him.

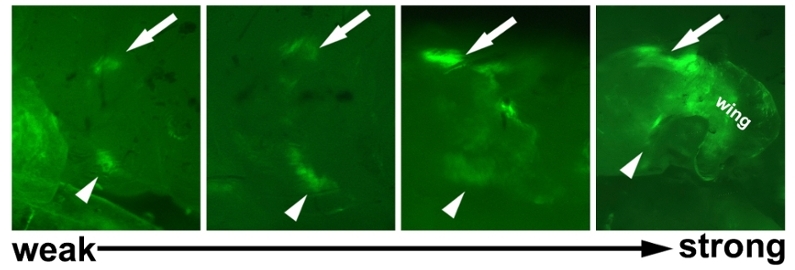

Image showing a transformation gradient of two groups of cells merging to form ectopic abdominal wings in Tribolium larvae (by David Linz).

5. The value of side projects and curiosity: A graduate student's perspective

David Linz (Miami ‘10, Ph.D. ’17), former doctoral student with Tomoyasu and current postdoctoral researcher at Indiana University, led a study on the dual-origin of insect wings published earlier this year in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences.

In this study they manipulated gene functions in Tribolium larvae and created a beetle with wings growing on its abdomen. The results offer further evidence supporting a dual evolutionary origin of insect wings.

This study grew out of a side project Linz was curious about. As he explains in a "behind the paper" story, Can a beetle with 12 extra wings help explore the evolutionary origin of insect wings? for Nature Research Ecology & Evolution:

Sharing their enthusiasm for beetles: Tomoyasu and his lab group talked with Talawanda High School students about insect wings and beetles (Tweet by Yoshi Tomoyasu).

“Every graduate student is told about the value of side projects. You just never know when some unexpected data might transform into something exciting. These glowing “blobs” of cells throughout the abdomen were, confusingly, little pockets of wing tissue where they shouldn’t be."

"I must say, the lens of hindsight is always clear, but at the time we didn’t realize it would take another year of thinking and experimentation before these data started to tell a story,” Linz wrote.

“Insect wings are a famous, yet mysterious morphological novelty, and I wouldn’t have guessed that fivve years ago some green blobs on the abdomen of beetles could help contribute to resolving this longstanding biological conundrum,” Linz said.

“This project taught me the importance of perseverance, and cautious but careful observation, but most importantly it taught me the value of raw curiosity.”

6. Learn to love beetles

Currently, eight undergraduates — including Moe — are enjoying insects and conducting research in Tomoyasu’s lab. They work with three graduate students and Shuxia Yi, adjunct professor of biology and research associate.

Learn more from his blog at blogs.miamioh.edu/tomoyasulab.