Fine-tuning music in motion

Professors in Music and Kinesiology are mapping violinists’ playing techniques to prevent overuse injuries and improve performance habits

•

Published

•

Violin professor Harvey Thurmer proposed an idea to the Kinesiology department’s Mark Walsh that sparked an interdisciplinary partnership between music and movement.

Fine-tuning music in motion

Professors in Music and Kinesiology are mapping violinists’ playing techniques to prevent overuse injuries and improve performance habits

•

Published

•

Arts, sciences, humanities, research, business – each separated by academic degrees and often distance on campus, but these disciplines do not exist in a bubble. Miami University’s interdisciplinary education lets students, faculty, and the community come together to simulate real-world collaboration, creating connections across the quad.

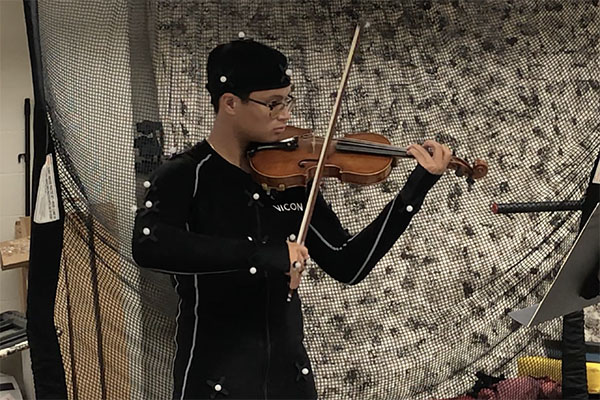

In this edition of Across the Quad, Violin professor Harvey Thurmer proposed an idea to the Kinesiology department’s Mark Walsh that sparked an interdisciplinary partnership between music and movement. Musicians, like athletes, are performers, and motion capture technology and kinesthetics can tell the story of how a violinist may be developing habitual injuries and poor playing techniques.

How did this collaboration come about?

Harvey Thurmer: I teach a class called The Alexander Technique, which is a body-mind modality that started in the performing arts but has leaked out into all kinds of other areas, including sports. It got me thinking about the intersection of kinesiology, and I've wanted to get into this lab of Mark's for years. I came across a study that had been done at the University of Maryland, and I sent it to Mark and said, “Think we could get anything like this started here?”

Mark Walsh: A lot of what we do in our biomechanics lab is motion capture. We put reflective markers on various body landmarks of usually athletes, but not always. And our software and cameras allow us to capture their movement and make a three-dimensional stick figure of them in our computer. Then we can give them advice on how to improve their technique, improve their performance, or maybe to change their technique to reduce the chance of injury. Like I said, we do mostly athletes, but we had a dog in once and mapped a dog gait to help design an artificial leg for a dog missing a leg.

Thurmer: Dogs and violins!

How does motion capture benefit violinists?

Thurmer: I'm using it to help my students get a physical and mental picture of the movements or habitual patterns of movement that they learned that are preventing them from progressing. I'm always looking for a new way into their thinking about choices they have that they may have never considered and seeing an avatar of themselves can often be a new avenue of discovery. I'm always dealing with the intersection of movement, sound, evaluation of sound, interpretation of the language of dots on a page; it's like a foreign language. There's so many systems that have to be coming together at once that I often find it's easiest to start with getting them kinesthetically aware of what they're actually doing; what parts of them need to work and which parts don't need to work. That's where I feel like the motion capture can really isolate parts of them that are not moving optimally.

Walsh: Habitual patterns can create overuse injuries. It’s what we call doing something that's a little bit wrong, but it's not enough to create acute injury. But, if you do it wrong long enough and it has a cumulative effect, then eventually there's some pathology caused by it.

How else are students getting involved and learning from this collaboration?

Walsh: There's nothing I do in the lab where my students aren’t involved. Every publication, every study, anything I do in the lab, I have students help me. I think it's just good to have hands-on experience using all of the equipment and technology.

This technology is not new, but this application might be. We use the same kind of software that we use to make animations for video games and movies. Combining this with music might be a little more new than traditional. As far as my students go, they dig it. It just gives them a little more information on projects that might be performed in the private sector and the variety of applications that are possible with our technology.

Thurmer: We're very much in the beginning stages of this project. My students are all thrilled to do anything that is cool and neat – something new and not just about whether you’re flat or sharp. Musicians are typically not trained to know things about their skeletons. I didn’t have a minute of human physiology, biomechanics, or anatomy in my musical training. And yet, just as much as I've scratched the surface, everything has changed.

Walsh: Once we’ve put the markers on students and we've calibrated the space, they can see their stick figure on the screen in real time while doing their thing. We can take that avatar, we can turn it, look at any side or the top. We can take it and slow it down or speed it up. All in real time. So it's informational, but it's also just fun and cool to have that stick figure there of you that's moving in real time. I think they get something out of it but also have some fun.

This project is in the early stages; where does it go from here?

Thurmer: There's even more options available than there were last semester in terms of capturing more angles and isolating specific parts. I'm not a scientist, but I think one of the exciting possibilities of how it could develop is what I've seen happen at another school in Maryland. They’ve got this technology connected to computer science and developed a software application where a student could record themselves on their phone and evaluate it with this technology themselves. We're not there yet, but for now, even what we are doing has the potential to be transformational for my students.

Anything to add?

Thurmer: This is the kind of thing that can happen here at Miami in particular just because we can walk across the quad, and I did. I found out about Mark's lab and bugged him for years about it. I think this kind of collaboration between disciplines is something that can be unique. Not that it doesn’t happen in other places, but it could lead to curricular collaborations that would expand options for students.

Walsh: Whether you're a golfer or a violinist, you have to prepare and deal with stress and everything else. You have to stay within yourself and do your thing. I had never thought about the connections; there's way more similarities than there are differences between athletic performance and musical performance. There are connections all over the place, but the trick is, knowing where to look to find them. Harvey did a great job and found that, and we collaborated. There are definitely places in every department that can complement what we're doing or what other departments are doing. The trick is finding them.

Thurmer: And, you have to step outside of the box that you're inevitably put in order to grow or to innovate in your discipline.

Walsh: That's a good point. I think it's cool, I think it's fun, and it gets my students experience in the lab. I think it's worthwhile.

In this edition of Across the Quad, Violin professor Harvey Thurmer proposed an idea to the Kinesiology department’s Mark Walsh that sparked an interdisciplinary partnership between music and movement. Musicians, like athletes, are performers, and motion capture technology and kinesthetics can tell the story of how a violinist may be developing habitual injuries and poor playing techniques.

How did this collaboration come about?

Harvey Thurmer: I teach a class called The Alexander Technique, which is a body-mind modality that started in the performing arts but has leaked out into all kinds of other areas, including sports. It got me thinking about the intersection of kinesiology, and I've wanted to get into this lab of Mark's for years. I came across a study that had been done at the University of Maryland, and I sent it to Mark and said, “Think we could get anything like this started here?”

Mark Walsh: A lot of what we do in our biomechanics lab is motion capture. We put reflective markers on various body landmarks of usually athletes, but not always. And our software and cameras allow us to capture their movement and make a three-dimensional stick figure of them in our computer. Then we can give them advice on how to improve their technique, improve their performance, or maybe to change their technique to reduce the chance of injury. Like I said, we do mostly athletes, but we had a dog in once and mapped a dog gait to help design an artificial leg for a dog missing a leg.

Thurmer: Dogs and violins!

How does motion capture benefit violinists?

Thurmer: I'm using it to help my students get a physical and mental picture of the movements or habitual patterns of movement that they learned that are preventing them from progressing. I'm always looking for a new way into their thinking about choices they have that they may have never considered and seeing an avatar of themselves can often be a new avenue of discovery. I'm always dealing with the intersection of movement, sound, evaluation of sound, interpretation of the language of dots on a page; it's like a foreign language. There's so many systems that have to be coming together at once that I often find it's easiest to start with getting them kinesthetically aware of what they're actually doing; what parts of them need to work and which parts don't need to work. That's where I feel like the motion capture can really isolate parts of them that are not moving optimally.

Walsh: Habitual patterns can create overuse injuries. It’s what we call doing something that's a little bit wrong, but it's not enough to create acute injury. But, if you do it wrong long enough and it has a cumulative effect, then eventually there's some pathology caused by it.

How else are students getting involved and learning from this collaboration?

Walsh: There's nothing I do in the lab where my students aren’t involved. Every publication, every study, anything I do in the lab, I have students help me. I think it's just good to have hands-on experience using all of the equipment and technology.

This technology is not new, but this application might be. We use the same kind of software that we use to make animations for video games and movies. Combining this with music might be a little more new than traditional. As far as my students go, they dig it. It just gives them a little more information on projects that might be performed in the private sector and the variety of applications that are possible with our technology.

Thurmer: We're very much in the beginning stages of this project. My students are all thrilled to do anything that is cool and neat – something new and not just about whether you’re flat or sharp. Musicians are typically not trained to know things about their skeletons. I didn’t have a minute of human physiology, biomechanics, or anatomy in my musical training. And yet, just as much as I've scratched the surface, everything has changed.

Walsh: Once we’ve put the markers on students and we've calibrated the space, they can see their stick figure on the screen in real time while doing their thing. We can take that avatar, we can turn it, look at any side or the top. We can take it and slow it down or speed it up. All in real time. So it's informational, but it's also just fun and cool to have that stick figure there of you that's moving in real time. I think they get something out of it but also have some fun.

This project is in the early stages; where does it go from here?

Thurmer: There's even more options available than there were last semester in terms of capturing more angles and isolating specific parts. I'm not a scientist, but I think one of the exciting possibilities of how it could develop is what I've seen happen at another school in Maryland. They’ve got this technology connected to computer science and developed a software application where a student could record themselves on their phone and evaluate it with this technology themselves. We're not there yet, but for now, even what we are doing has the potential to be transformational for my students.

Anything to add?

Thurmer: This is the kind of thing that can happen here at Miami in particular just because we can walk across the quad, and I did. I found out about Mark's lab and bugged him for years about it. I think this kind of collaboration between disciplines is something that can be unique. Not that it doesn’t happen in other places, but it could lead to curricular collaborations that would expand options for students.

Walsh: Whether you're a golfer or a violinist, you have to prepare and deal with stress and everything else. You have to stay within yourself and do your thing. I had never thought about the connections; there's way more similarities than there are differences between athletic performance and musical performance. There are connections all over the place, but the trick is, knowing where to look to find them. Harvey did a great job and found that, and we collaborated. There are definitely places in every department that can complement what we're doing or what other departments are doing. The trick is finding them.

Thurmer: And, you have to step outside of the box that you're inevitably put in order to grow or to innovate in your discipline.

Walsh: That's a good point. I think it's cool, I think it's fun, and it gets my students experience in the lab. I think it's worthwhile.

Established in 1809, Miami University is located in Oxford, Ohio, with regional campuses in Hamilton and Middletown, a learning center in West Chester, and a European study center in Luxembourg.