Miami brain cell research could lead to targeted therapies for autism

Miami neuroscience research duo discovered how to restore electrical activity in brain cells linked to autism spectrum disorder

Miami brain cell research could lead to targeted therapies for autism

Joseph Ransdell, assistant professor of Biology, and Samuel Brown,’19, doctoral candidate in Biology, focused their research on a specific type of brain cell called Purkinje neurons. These cells, located in the cerebellum —the part of the brain that coordinates movement — are important for motor control, balance and coordination. Being able to walk in a straight line, pick up a cup of coffee without spilling it, and maintaining balance on a moving bus are all thanks to Purkinje neurons.

Ransdell and Brown discovered that in mice with autism-like symptoms, these Purkinje neurons weren’t working normally due to a deficit in a protein called a sodium channel. These channels act as gates to help generate electrical signals, but when these gates don’t work properly, communication between brain cells breaks down.

Through their experiments, they were able to not only identify what had gone wrong with these neurons, but also that they could be restored to normal functioning.

Their methods article, “Dynamic Clamp Methods to Investigate Impaired Neuronal Excitability Associated with Autism”, was published in the scientific video journal this fall.

“We were able to directly show that when we add back the correct type of sodium channel properties to these impaired or mutated Purkinje neurons, we can rescue their electrical activity,” Ransdell said.“We can make them look more like typical Purkinje neurons in terms of their electrical activity.”

To confirm their findings, Ransdell and Brown ran the experiment in reverse. Using computer simulations, they took healthy Purkinje neurons and artificially introduced the same sodium channel defects. These previously healthy neurons developed the same impaired electrical activity, demonstrating that the faulty sodium channels are the root cause.

This discovery could lead to targeted therapeutics not just for autism, but for a range of nervous system disorders including depression, bipolar disorder, and schizophrenia — all disorders where problems in brain cell electrical signaling may play a role.

“Now that we have a clear and cohesive understanding that it’s a deficit in sodium channels driving the problems in these Purkinje neurons, future investigators can target those channels to develop therapeutics,” Ransdell said.

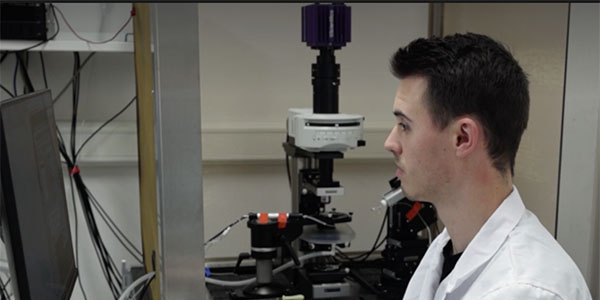

The duo are able to study a neuron’s electrical behavior in real-time using an experimental technique known as dynamic clamp electrophysiology. A slice of mouse brain tissue is kept alive under a microscope using a constant flow of synthetic cerebral spinal fluid. They then connect glass microelectrodes directly to individual Purkinje neurons. The pipettes act as electrodes that can simulate artificial sodium channels, allowing them to test what happens to the neuron’s electrical activity when they restore the missing protein. All electrical activity is recorded and uploaded to a computer.

Dynamic clamp electrophysiology is not only an incredibly delicate process - most of the method is conducted on an anti-vibration table to ensure the electrical readings are accurate even if something were to be bumped - it’s also incredibly complex. Researchers can find techniques like this hard to replicate when they only have written documentation to guide them through the process, even if they’ve visited a lab to see how the technique is performed. This is where JoVE comes in.

JoVE’s mission is to improve scientific research and education by producing videos filming the steps of cutting-edge experiments, allowing researchers to expand the technique range of their laboratories.

Brown described the journal as the YouTube of science methods: “With scientific protocols, some of these techniques are really elaborate and have a lot of very involved steps. If I wanted to search up a particular technique, I could do that with JoVE and try to follow step by step.”

Having their work published through JoVE will help other investigators and advance the research for therapeutics. Ransdell also commented on their ability to perform a cutting-edge technique like dynamic clamp electrophysiology here at Miami.

“We’re perfectly capable of doing this sophisticated method at Miami. We don’t need a dramatic clinical or medical school setting to do this kind of really advanced neuroscience technique,” said Ransdell. “It’s a powerful method, but it’s also really well suited for what we do best at Miami, which is getting undergraduates and graduate students into doing high end science.”

Brown, who graduated in 2019 with a Biology major and neuroscience co-major, was involved in undergraduate research with neuroscientist Lori Isaacson, professor of Biology (now retired).